Medea Re-Versed, co-conceived by Luis Quintero and Nathan Winkelstein, gives Euripides’ ancient tragedy hip-hop vibes. Directed by Winkelstein, this coproduction by the Off-Broadway companies Red Bull Theater and Bedlam aims to expand the traditional theater audience—and with the dynamic Sarin Monae West as the princess and sorceress, it’s likely to succeed.

SuperHero

SuperHero began performances the day after a gunman opened fire aboard a rush-hour Brooklyn subway train, giving added resonance to its protagonist’s decision to eschew violence as a response to personal turmoil. The playwriting debut of actor Ian Eaton, SuperHero is an autobiographical coming-of-age story about an awkward, overweight boy growing up in the Harlem projects in the 1980s.

Sister Calling My Name

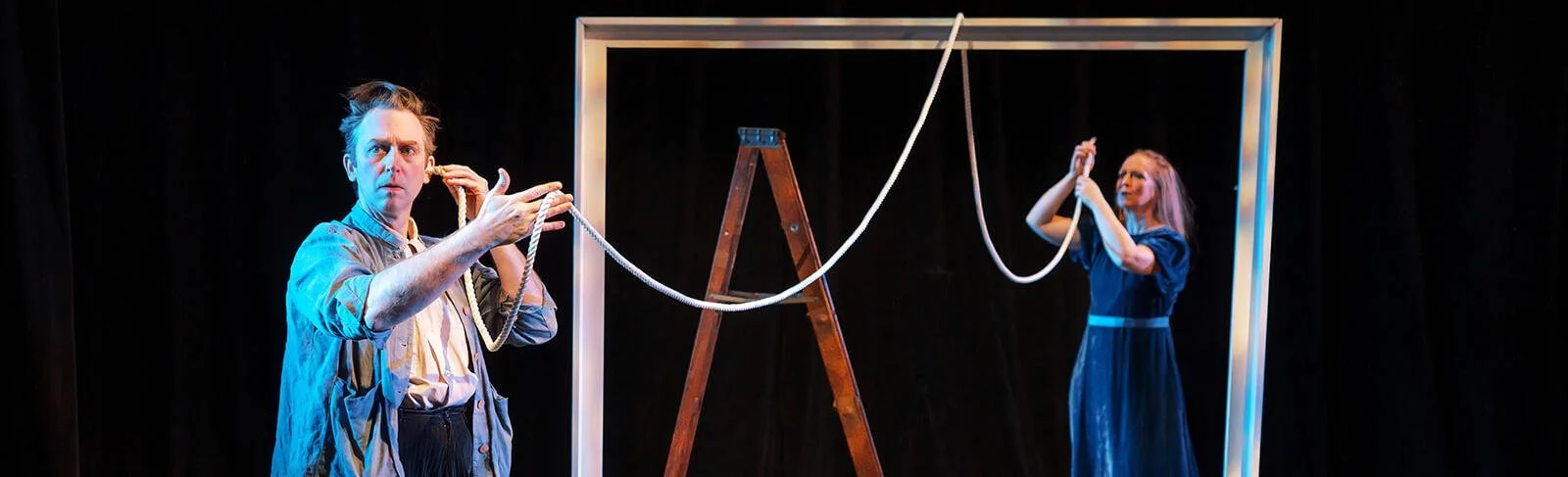

Buzz McLaughlin’s 1996 play, Sister Calling My Name, tells a familial story of loss, love and forgiveness. At the center is Michael (John Marshall) an English literature professor whose life has not gone according to his expectations. He has recently undergone a divorce and been denied tenure, and the last thing he wants to do is visit his mentally disabled sister Lindsey (Gillian Todd), who made his life extremely difficult growing up.

All Our Children

All Our Children, the first play by the experienced theater and opera director Stephen Unwin, is structured as a moral debate that sheds light on the mass murder of disabled children in Nazi Germany. The play is well-staged and intermittently powerful, but overly schematic, as the characters too often feel like mouthpieces rather than fully realized individuals. It premiered on the West End in London in 2017, and now comes to the Black Box Theater at the Sheen Center, with a new cast, under the sure-handed direction of Ethan McSweeny.

Little Rock

Little Rock, Rajendra Ramoon Maharaj’s docudrama about the nine African American students who integrated a white high school in the Arkansas capital in 1957, seems especially relevant now. Near the end of the play, an actor assuming the persona of television news reporter Mike Wallace says, “It’s astonishing what the Nine from Little Rock have taught us as a people—that even children can, in a gentle way, shake the world for better.” It remains an important lesson today as schools face new and presumably insurmountable challenges. Indeed, as the inspirational and courageously outspoken Parkland, Fla., shooting survivors continue to demonstrate, adults can learn a great deal about social change and agitation from the youth.

Luft Gangster

Lowell Byers’s play Luft Gangster was inspired by the real-life story of Louis Fowler, a waist gunner during World War II. The play opens on a tender scene between Lou (played by Byers himself with a wonderful mix of stoicism and sincerity), and his mother, who is clearly sick or mentally ill. Louis’s father is long dead, and when his mother dies, he enlists to fight. His plane is shot down and he is captured and interrogated by the Nazis, but they don’t get a word out of him. At first he’s put in a makeshift holding cell where he is joined by another flier, Joe, played with a wonderful earnestness by Sean Hoagland, who doubts they’ll get out alive. Lou tells him, “I don’t think it’s my time to go.” Joe retorts: “I just hope they know that.”

Template for an Epidemic

The adventurous Playhouse Creatures Theatre Company is offering what’s labeled a “20th anniversary production” of Naomi Wallace’s One Flea Spare. This mordant historical drama didn't actually arrive in New York until 1997. It was a critical favorite at the 1996 Humana Festival of New American Plays in the playwright's hometown, Louisville, Ky.; and word of mouth from the Festival made its subsequent engagement at the Joseph Papp Public Theater one of the most anticipated events of the theater season. One Flea Spare, which derives its title from a poem by John Donne, is set in 1665 and portrays four people—a married couple and two strangers—trapped in a house that’s under quarantine. The place is the London of Daniel Defoe’s AJournal of the Plague Year, a work of fiction, which, Wallace has said, inspired the imaginative universe of her play. The current revival, directed by Caitlin McLeod and performed by a fine quintet of actors, is two relentless hours of powerful, if markedly cerebral, dialogue, with a number of narrative surprises for the first-time viewer.

Wallace wrote One Flea Spare in the midst of the AIDS epidemic, a public-health crisis that profoundly affected the American and British theater communities (and continues to do so). At that point, those infected with HIV had little expectation of longevity and those living with AIDS were subject to prejudice and a myriad of injustices. Defoe’s great novel and its portrait of plague-ravaged London was a natural point of historical reference for an erudite writer contemplating modern men and women contending with the spread of inexplicable disease.

In One Flea Spare, William and Darcy Snelgrave (Gordon Joseph Weiss and Concetta Tomei) are childless aristocrats whose home has been quarantined after the death of their servants from bubonic plague. Just as the Snelgraves are about to be released from forced isolation (which would allow them to flee London for the peace and presumed safety of the countryside), their premises are invaded by Bunce (Joseph W. Rodrigues), a virile, coarse-mannered sailor, and Morse (Remy Zaken), a 12-year-old servant disguised as the daughter of the upper-crust family whom she previously served. Both are seeking asylum from infection and the police.

The interlopers are a catastrophe for the Snelgraves. A municipal guard (Donte Bonner), charged with monitoring neighborhood compliance with hygiene regulations, sees them, bars the residence doors, and extends the quarantine. This means that four people from differing social strata of a rigidly hierarchical society must endure 28 days together in the closest quarters imaginable. As the play proceeds, the high-testosterone presence of Bunce unsettles the sex-starved Snelgraves and awakens unaccustomed responses in the pubescent Morse. Under stress of confinement, the characters' secrets and prejudices slip out, their yearnings boil up, and civility evaporates in the heat of compulsive drives and desires.

Scenic designer Bryce Cutler has configured the Sheen Center's black-box venue for intimate theater-in-the-round, with minimal space between actors and audience. The principal feature of his simple, handsome stage set is a tiny, raised platform on which the bulk of the action is played. Four of the five actors are crowded in that little square for much of the performance, while Bonner, playing the sole character not confined to the house, wanders around outside the square, addressing the other actors from a lower level that represents the street.

Sarafina Bush dresses the actors in drab-hued costumes that combine contemporary garments with items suggesting 17th-century style. Aaron Porter illuminates the stage in cold, wintry light. The effect of the creative team's design is a sense of unrelenting claustrophobia.

Wallace is an artist of extremes. Her characters are altruistic one minute, predatory the next. The dialogue veers precipitously from poetic to crass and profane. The effect of her prose is as often chilly as it is sensual. Her writing often soars with an operatic quality, fraught with emotion, that captures the characters’ sexual longing yet expresses the trauma created by their radical separation from the rest of the world. McLeod has staged the play with a great deal of dance-like movement that complements the musicality of Wallace’s text and depicts the play's eroticism and violence vividly but with a certain delicacy. Despite occasional lapses in dialect, the five actors handle the lyrical qualities of the playwright's lines and speeches effectively and function throughout as a balanced ensemble.

When One Flea Spare premiered at the Humana Festival, Wallace had already made a name for herself in Britain but was unfamiliar in her native land. During the past two decades, she has become well-known, at least for a playwright, in the United States. She has received a "genius grant" from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation (possibly the most enviable honor in the English-speaking world); and, since 2009, One Flea Spare has been the sole work by a living American author in the repertoire of the Comédie-Française, the French national theater. The current revival makes a strong case for One Flea Spare as the original, insightful work the critics judged it to be 20 years ago in Louisville and an enduring part of postmodernist drama.

Naomi Wallace’s One Flea Spare plays at the Sheen Center (18 Bleecker St.) through Nov. 13. Evening performances are at 8 p.m. Wednesday through Saturday; matinees are at 2 p.m. Saturdays and 3 p.m. Sundays. Tickets may be purchased by calling the box office at (212) 925-2812 or visiting sheencenter.org/shows/one-flea-spare/.