Charles Dickens may have resurrected the tradition of telling tales guaranteed to cause fright on Christmas Eve, but RadioTheatre and Dan Bianchi are giving Dickens a run for his money.

Giving gifts, singing carols and sending generic holiday cards are the norm each year, but it seems the culture of telling ghost stories at Christmas has become lost over several decades. Set in old Manhattan and told during RadioTheatre’s late-night broadcast, Bianchi, and director R. Patrick Alberty awaken imaginations and create a supernatural experience in the most simplistic way with Ghosts of Christmas Past.

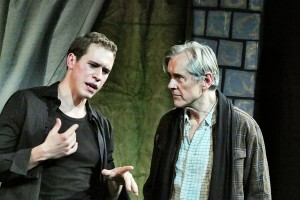

The stage is set for four — the host narrates from tale to tale while three storytellers move seamlessly from character to character. As director of sound and music, Bianchi allows listeners and viewers to imagine a setting fit for six ghostly tales. Frank Zilinyl, R. Patrick Alberty, Adam Segaller and Zoe V. Speas are dressed in all black, lurking in the shadows. Speas’s makeup is beautiful but hauntingly pale. The snowstorm outside helped to create a dark and drafty theater with a red, gigantic skull as the backdrop, adding the perfect touch.

As the dial is turned to RadioTheatre, the host’s (Zilinyl) voice is eerie from the outset. “It Happened On Christmas” highlights just how busy and jaded the typical New Yorker can be. Mr. Carter (Alberty) runs into the super, Mr. Beasley (Segaller), while on his way to church on Christmas Day; Beasley’s on his way up to the roof to “check on the pigeons.” Shortly after, Mrs. Cacciatore (Speas) hysterically screams to her neighbors that she’s seen Beasley fall from the roof to his death, everyone laughs and brushes her off. Why wouldn’t they? His body has disappeared. A man doesn’t get up and walk away, after falling stories to his death. Does he? It isn't until the tenants of the building need their super, that they realize he is in fact dead, and missing…

Written to be a little less dark, “A Wonderful Crazy” begins with the often-unbelievable fact, that most people do not enjoy Christmas. On Christmas Eve, John (Segaller), bombarded with debt and despair, spends his holiday at a bar. An old friend, Mike (Alberty), shows up and offers his checkbook and a chance at love. John is baffled — how does John know Linda (Speas) is his heart’s desire? Why is he offering him a second chance at life? The bartender (Zilinyl) drops a major bomb on John, causing him to evaluate everything that’s happened in his past and what’s in store for Linda and his future, proving not all ghosts are haunting Zilinyl — giving hope that guardian angles do exist.

“The Calling” literally causes chills down the spine. Taking place in 1911, a young man (Segaller) loses his wife after she goes to work at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory; she leaps to her death after being caught in the infamous fire. Nine months later on Christmas Eve, he sets the table, prepares an elaborate meal and awaits her return. Sound effects paint a mental picture of a spirit entering the hallway as a neighbor’s dog howls at the wind. Horrified by her ghostly presence that is not like that of his wife’s, he cowards away. The narrator (Speas) has the ability to grasp the audience’s spirit so that they’ll hang on her every word, spinning the fear of the deceased wife, to anger at the uninviting husband; angry that he is gutless and causes his love to flee, when all she wanted was warmth and love. It is absolutely magnificent.

During the conclusion, the host drops a hint that they wish to broadcast every year during RadioTheatre, keeping with the Victorian tradition of celebrating Christmas among the supernatural. Bianchi hopes to return next year with more ghastly folklore. As long as the dead keep on living, New York is sure to tune-in, embracing the paranormal in the East Village.

RadioTheatre's Ghosts of Christmas Past presented by the Horse Trade Theater Group at The Kraine Theater (85 East 4th Street) runs through Jan. 12. The following schedule is current: Sunday, Dec. 29 at 3 p.m., Wednesday, Jan. 8 at 8 p.m., Saturday, Jan. 11 at 6 p.m. and Sunday, Jan. 12 at 6 p.m. General admission is $18 and $15 for students. Tickets may be purchased by calling Smarttix at 212-868-4444 or are available online at www.horsetrade.info.