In Honor Molloy's Crackskull Row, a hovel in Dublin becomes the unlikely setting for an emotionally overwrought, Oedipal drama. The play is set in 1999, but it has the audience fooled—Molloy's play has all the trappings of a mid-20th-century, Joycean family narrative. Although the audience often hears references to staples of modern life—mobile phones, an ESB (Electricity Supply Board) company, even Oxfam—they sound anachronistic against this landscape of aged, mournful nostalgia. But for all its old-world charm, Molloy's riveting words don't translate perfectly to the stage. Directed by a courageous Kira Simring and staged by the cell at the Workshop Theatre, this beautifully written, hauntingly poetic story struggles to find the right tongues for its finely crafted words.

The production opens with the dour throb of a drum and that sprightly music so unique to the Irish musical tradition. An old man named Rasher/Basher, played by Colin Lane, enters, a lone figure with light streaming around him, and says that the sound we hear is "the thrum of the bodhran." It is a kind of Irish drum, well-known for its dooming, thumping sound. He talks wearily, anxiously, about his past, saying that his 'Da' was a musician, and that, although he's been away from home for 33 years, he's become the "spit and shite" of his father's likeness. A sense of foreboding takes hold, the rhythm of the bodhran notwithstanding. Then we see the ramshackle insides of a Dublin home. A vast, untidy sofa, wooden walls with peeling plaster, and a film of dirt covering the kitchen all clue us into the premise of Crackskull Row: a home has been leveled by the passage of time but seems ripe for renewed activity.

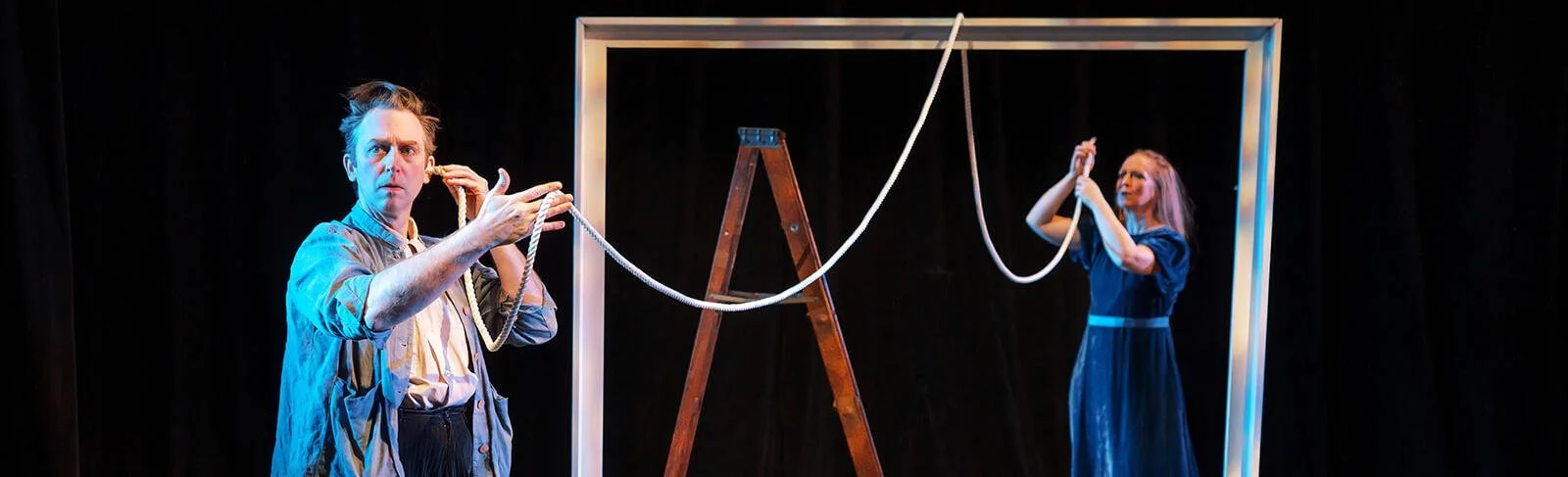

What follows is a disturbing but absorbing puzzle about Rasher Moorigan (John Charles McLaughlin), his father Basher (Lane, who also plays the older Rasher), mother Masher (Terry Donnelly) and daughter Dolly (Gina Costigan). Masher is almost literally rotting inside her electricity-less, plumbing-less home on Crackskull Row, her bills from the ESB piling up on the sofa. And while her past bothers her terribly, she is saved by the remembrance of her son, Rasher, and the sustenance of her daughter, Dolly. But it's soon apparent that the narrator, an aged Rasher, himself is unreliable, as are one's eyes and ears. Personae are fluid; the four players inhabit other bodies, take on different accents, and change their clothes easily. Suffice it to say that Rasher and Masher Moorigan are hiding a lethal, 30-year-old secret, the reverberations of which are still knocking around in their battered skulls.

There is much to admire about the production, including some fine performances from John Charles McLaughlin, who plays a young, on-edge, perversely romantic Rasher, and Gina Costigan, whose Dolly is a complex, willful thing. But their enthusiasm doesn't quite make up for the uneasy adaptation from script to stage. Crackskull Row often values dramatic potential over clarity, and while some climactic, intimate scenes (like Rasher's interactions with Dolly, or the dying moments of the play) are intensely dramatic, others fall into a spasmodic mode of meaningless activity. The result is not just an abrogation of Molloy's authorial intent for Crackskull Row, but a confusingly paced, occasionally overwrought performance.

Save for a few rare scenes of sparkling chemistry, the production threatens to come away at the seams. Molloy's dialogue is chock-full of intelligent wordplay, quick humor, and wit, but combined with the Irish brogue and quick delivery, her words (when delivered on stage) take a while to register. As a result, the enjoyment of the play is temporarily stunted. Much of the magic that can be read in Molloy's teasing, metaphorical writing is either difficult to find or nonexistent in the staging. We happen upon the wordplay, or a throwaway malapropism, a little too late to derive a complete appreciation of the story.

Yet, the production is redeemed and revived by its flowing, narrative core, and the actors who bring it to life. The chemistry between McLaughlin and Costigan is palpable; it's not for nothing that the Masher-Rasher relationship is central to the play. Lane brings a nostalgic weariness to his role, and lends a dreamy gravitas to the production. But it is Costigan who bears much of Molloy's light-hearted darkness from the page to the stage; she plays Dolly with riveting, minimalist understanding. Even her mirror, Terry Donnelly's Masher, does not waste a single movement (although words seem to be held in lower regard). To help us forget this latter discourtesy, M. Florian Staab (responsible for all the original music and sound design) punctuates scene changes with welcome percussion and fiddle-song. In moments of stillness or silence, there is Daniel Geggatt’s set to appreciate, in blue, brown and yellow, seeming for all intents and purposes like a living thing. As for the other living things taking the stage, they—and the playwright—are among the only reasons you should take a trip to the Workshop Theater this week.

The cell's production of Crackskull Row runs through Sept. 25. Evening performances are at 7 p.m. Thursday through Saturday; matinees are at 3 p.m. Saturday and Sunday. There are additional performances at 7 p.m. on Sept. 14 and 21. The Main Stage of the Workshop Theatre is at 312 West 36th St. (between Eighth and Ninth avenues). Tickets are $25. For more information about the show and tickets, visit www.thecelltheatre.org.