The Tragical History of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark is the longest of William Shakespeare’s 36 plays and probably the most complex. In the four centuries since the Lord Chamberlain’s Men (the band of players to which the Bard belonged) first presented Hamlet, critics have expended countless gallons of ink debating the play's strengths and flaws. Harold Bloom calls Hamlet “our world’s most advanced drama, imitated but scarcely transcended by Ibsen, Chekhov, Pirandello and Beckett.” T.S. Eliot finds the play “puzzling” and “disquieting,” and declares that, “far from being Shakespeare’s masterpiece,” it's “an artistic failure.” The fact that Hamlet is Shakespeare’s most frequently produced work indicates that audiences, on the whole, are less skeptical of its merits than Eliot.

The contours of Prince Hamlet’s story come from Historia Danica by Saxo Grammaticus and Belleforest's Histoires Tragiques. Shakespeare remolded the existing material to the shape of the English revenge tragedies popular in his day. The result, as always with Shakespeare, is altogether different from the sources on which the playwright drew. In Shakespeare’s version, Hamlet, a student at the University of Wittenberg, has returned to Denmark for his father's funeral. By a ghostly visitation (the Ghost being his father, the late King), Hamlet receives a piece of life-changing news: the King didn’t die from a snakebite, as generally believed; he was poisoned by Claudius, the new king who is Hamlet’s paternal uncle and now his stepfather. The social strictures of the day demand that the son avenge the parent's death; yet, for most of the play, Hamlet procrastinates, keening over his loss, fuming about his mother’s swift re-marriage to the avaricious uncle, pondering mortality and that “undiscovered country from whose bourn / no traveler returns.” He masks his intentions and his real emotions with an "antic disposition."

On Manhattan's Upper West Side, the small, ambitious Frog and Peach Theatre Company is offering Hamlet with a film-noir flavor that enhances the mysterious qualities of Shakespeare's plot and underscores what's most suspenseful in the dialogue. The Frog and Peach Hamlet gets off to a sluggish start but, as the student-prince figures out what's rotten in Denmark, the pace accelerates. After a single intermission (which falls surprisingly early in the proceedings), the action moves with a sense of inexorability toward the company's engrossing enactment of the duel scene, with its moving reversals and many deaths. The cast — six members of the Actors' Equity Association and eight non-union performers — handles Shakespeare’s blank verse competently and, in some cases, with élan.

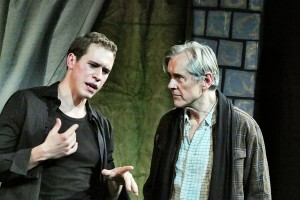

Brando Boniver plays Hamlet as a straight-shooter who's discovering how deceitful the world can be. He's a meditative sophomore, learning to dissemble for his own protection. Boniver's mixture of naivety and wisdom gives an interesting slant to the Prince's familiar monologues. Imposingly tall and clad, of course, in black, Boniver leavens Hamlet’s melancholy with considerable humor; here and there, he refreshes a well-known line with a dash of Millennial inflection. He delivers the play's most famous soliloquy — "to be, or not to be" — in feigned madness, waltzing Ophelia (Megan McGarvey) around the stage. This unexpected bit of blocking invigorates a passage that's familiar to the point of being stale; and, in this staging, the soliloquy works both as an expression of Hamlet's thoughts on the mortal condition and, from Ophelia's point of view, as a burst of creepy logorrhea about suicide.

As Horatio, Hamlet’s closest friend and the one who survives to tell the Prince's tale, Jonathan Reed Wexler is the very model of loyalty and comradely affection. Of all the cast, Wexler is most at ease with Shakespeare’s iambic pentameter. His unadorned delivery of the "flights of angels" speech, as well as the subsequent lines about the "carnal, bloody and unnatural acts" he has witnessed, provides a moving summary of all the preceding turmoil. It’s tempting to imagine what Wexler's vocal skill, unaffected style, and assured stage presence would bring to the title role.

Director Lynnea Benson has trimmed Shakespeare's text judiciously (the performance runs only slightly more than two and a half hours), and offers some interesting innovations. A single Player (Roger Rathburn) represents the traveling troupe that arrives in Elsinore to "catch the conscience of the King." To make this casting-efficiency work, Horatio joins Rathburn in the play-within-a-play; and Wexler, gussied up in tacky road-show finery, wrings considerable humor out of Horatio's consternation at being pressed by Hamlet into service as an amateur thespian.

Benson has cast Amy Frances Quint and Ilaria Amadasi as Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, Hamlet's supposed-friends from Wittenberg, invited to Denmark by Claudius to spy on the Prince. Quint and Amadasi are a couple of Bond Girls, too mature to be undergraduates (even if Wittenberg had enrolled women in those days). They simper and posture and paw Boniver like a pair of medieval Mrs. Robinsons. This non-traditional casting is a risky directorial gambit; but the louche qualities with which Quint and Amadasi imbue their characters make Rosencrantz and Guildenstern effective foils to Boniver's fundamentally ingenuous Hamlet. In most productions, Hamlet's emotionless sacrifice of the lives of his erstwhile friends is unnerving. In the Frog and Peach production, Quint and Amadasi are cold-hearted foxes outfoxed by the Prince; and their treachery proves a milestone in Hamlet's education about the dark side of humankind. It all makes sense.

Despite a few Nordic touches, the scenic design by Andy Estep is not committed to a particular locale; and the costumes by Lindsey L. Vandevier reflect no particular era. Both scenery and clothes have been managed admirably on a tight budget and, in their simplicity, serve their purpose well. Some weaknesses in the production may be a function of the church-basement nature of the The West End Theatre. Broadway veteran Dennis Parichy has to contend with a primitive lighting system; and the original score by Ian McDonald of King Crimson and Foreigner gets a less-than-fair hearing due to the abruptness of all the sound cues.

By the time Frog and Prince Company finishes its run, there will be other Hamlets competing for attention in the Tri-State area. In the weeks ahead, English actor Rory Kinnear (of Skyfall fame) will be seen in the title role at various cinemas in the region as the Royal National Theatre reprises its worldwide broadcast of the 2010 production; Kevin Kline is including material from Hamlet in his one-man show at the McCarter Theatre Center in Princeton; and the Bedlam Theatre Company will commence an open-ended run of its 4-actor Hamlet at the Culture Project on Bleecker Street. The prevalence of Shakespeare's greatest creation in and around New York this autumn confirms Harold Bloom's declaration: "There is no end to Hamlet or to Hamlet, because there is no end to Shakespeare."

William Shakespeare's Hamlet presented by The Frog and Peach Theatre Company at The West End Theatre (above the Church of St. Paul/St. Andrew, 236 West 86th Street) runs Thursdays, Fridays and Saturdays at 7:30 p.m., Sundays at 3 p.m., through Sunday, November 10. General admission $18; seniors and students $12.