No one attends the symphony for a surprise ending, or to watch the string section go rogue. The enjoyment lies in the way that each instrument performs as expected, to the height of the players’ abilities, creating controlled harmonies and disciplined rhythms that pull at the heart while being pleasing to the ear. So it is with Mrs. Murray’s Menagerie, the absorbing new comedy from The Mad Ones that finds six parents, each with an instantly recognizable personality, playing off one another during a market-research session at a pace that can only be described as musical.

A Jewish Joke

A Jewish Joke is a one-man show about partnerships, but that is just one of its several paradoxes. The play explores Jewish comedy, though from the serious viewpoint of its effect during the era of the Hollywood blacklist, when humor could either get a guy out of a jam, or reinforce anti-Semitic stereotypes. Many old jokes are told during the 90-minute production; however, they are delivered with such odd undertones that it is impossible to tell whether director David Ellenstein was hoping for legit laughter or uncomfortable sighs from the vintage zingers that are rife with sexism and prejudice. And Joke is a play about writing which, when it falters, does so because the script is, at times, contrived or repetitious. When it succeeds, it does so because Phil Johnson, of San Diego’s Roustabouts Theatre Company, so fully inhabits his role that his character’s stressed-out persona transcends the page.

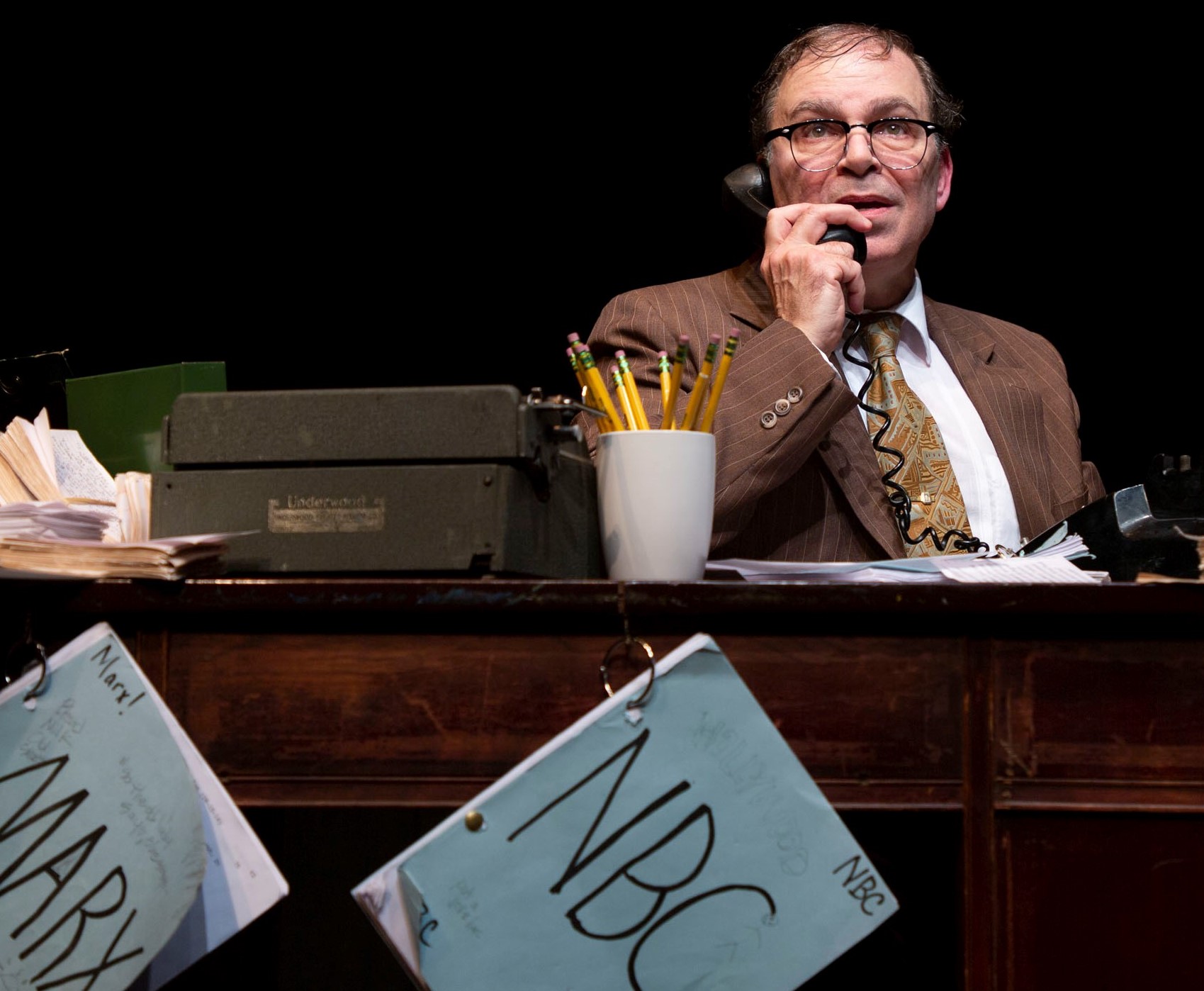

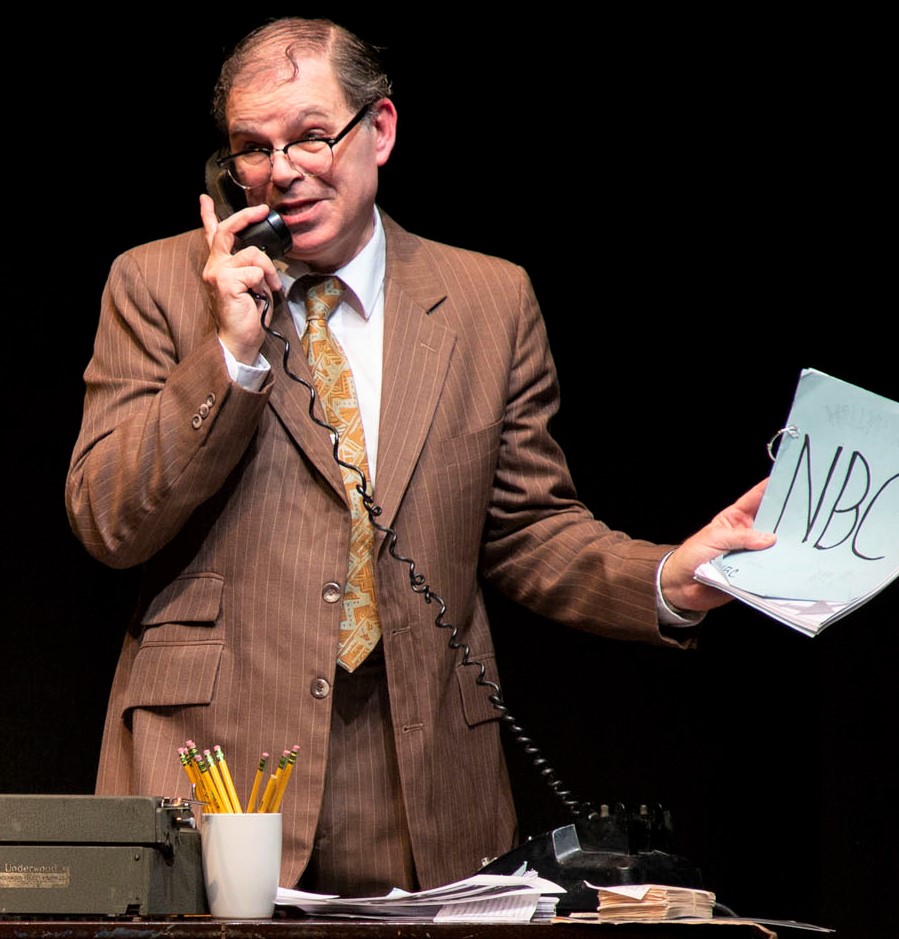

Phil Johnson as Bernie Lutz in A Jewish Joke, written by Johnson and Marni Freedman.

Johnson portrays Bernie Lutz, a film writer for MGM Studios in its mid-20th-century heyday. Though successful at his craft, he looks the worse for wear. His sad brown suit is wrinkled, his tie atrocious, his eyeglasses cheap, and his limp comb-over barely covers his scalp. He would be considered Kafkaesque, except that on this particular morning he finds he has been transformed into, not a cockroach, but a commie. His name, along with that of his lifelong friend and writing partner, Morris Frumsky, have turned up in Red Channels, the right-wing publication that, in 1950, accused scores of entertainers and journalists of having ties to the Communist Party (Real-life names cited by Red Channels ran the artistic gamut from Orson Welles to Dorothy Parker to Leonard Bernstein.).

It seems Morris had recently taken Bernie to a soirée that was more than just the cocktail-weenie extravaganza Bernie thought it to be. The fact that Morris is nowhere to be found as the play begins, despite the fact that their latest flick, The Big Casbah, is set to premiere that very evening, telegraphs all we need to know about Bernie’s impending doom. But Johnson, who co-wrote the piece with Marni Freedman, walks us through Bernie’s very bad day nonetheless. First, it turns out that the government had sent him a warning letter regarding the “important work of investigators under Senator Joseph McCarthy,” but he conveniently had torn it into three pieces without bothering to read it, allowing him to now build tension by slowly finding each section amid the piles of crumpled papers strewn about his bungalow. Then his colleagues begin disassociating. Danny Kaye shows him the door. Louis B. Mayer has no time for him. And when Harpo Marx gives him the silent treatment, he reaches a crisis point: testify against Morris to clear his own name, or protect his pal and risk sacrificing his career.

Bernie treads the fine line between comedy and tragedy. Photographs by Clay Anderson.

Without other characters in the room to play against, Bernie frequently turns to the audience and tells one of the many off-color gags he has collected on index cards. Most are groaners and, whether meant to be awful or not, they do keep the audience from becoming too emotionally caught up in Bernie’s dilemma. It’s the old “alienation effect,” a technique pioneered by another member of the Hollywood blacklist, Bertolt Brecht.

Bernie also has framed pictures of his wife and his parents with which to interact. But mostly, he is on the phone. Indeed, the plot revelations are entirely dependent on the seemingly endless number of calls that Bernie makes and receives. The playwrights employ a couple of devices to minimize the drudgery. Rather than repeatedly having to dial the rotary phone, Bernie has an unseen secretary place his calls. Somehow, she is able to do so with lightning speed, adding a surreal aspect to the evening. And Bernie answers the phone each time with a different one-liner (“Bernie’s Yacht Club”). None are particularly funny, but it beats enduring a hellacious string of hellos.

Production supervisor/designer Aaron Rumley provides a desk for Bernie to work behind, and I will just assume that its drawers are full. Why else install hooks across the front of it and glaringly hang from them the scripts that Bernie risks forfeiting? Regardless, Johnson, who has been touring and perfecting this role since 2016, when the show won Best Drama at the United Solo Fest NYC, makes it work, taking his character’s motto to heart: “When there is no mensch, be the mensch.”

A Jewish Joke, by Marni Freedman and Phil Johnson, runs through March 31 at The Lion Theater (410 W. 42nd St.). Evening performances are at 8 p.m. Wednesdays through Saturdays; matinees are at 3 p.m. Sundays. For tickets, call Telecharge at (212) 239-6200 or visit ajewishjoke.com.

Actually, We’re F**ked

Playwright Matt Williams created the TV series Roseanne, co-created the TV series Home Improvement, and was a writer on The Cosby Show, which is to say that the man knows a little something about domestic comedies in which hard-working parents love and nurture their large families. In his new play, Actually, We’re F**ked, he attempts to go in a different direction, exploring whether two young couples who are barely holding their marriages together can stop fretting, navel-gazing, and betraying each other long enough to have, or even want, a ch**d.

Trick or Treat

Ghosts and demons are expected to rise up on Halloween, and the ones within the haunted house of Jack Neary’s twisted and brutal tragicomedy, Trick or Treat, do not disappoint. The walking dead linger on the staircase while the spirits of deceased relatives, as well as some long-buried secrets, emerge to effectively tear apart a family. Hints of betrayal, mental illness and physical violence pervade the air, so don’t even ask what happened in the basement. Not that Neary’s characters are wearing white sheets, bloody robes or devil horns. No, this is a far scarier and more tragic clan: a passive-aggressive, Irish-American, middle-class family in eastern Massachusetts.

Set on Halloween, the play’s first act builds to an earthquake of a revelation, while Act II is a series of aftershocks that cause sustained damage. That listing the specifics would mean unmasking all the fun is testament to the integrity of Neary’s nifty script. The past and present actions of each family member are so tightly interwoven that to mention a father’s long-ago instinctual defense of his young son is to divulge why his daughter would grow up to marry the man she did. Suffice it to say that this is a play that pits paternal protection against marital devotion, and measures the stark difference between preserving the family and preserving the family name.

Claire (Jenni Putney) offers sympathy to her father (Gordon Clapp) after a hard day in Jack Neary’s Trick or Treat. Top: Teddy (David Mason) and Johnny (Clapp) in a difficult father-son moment. Photographs by Heidi Bohnenkamp.

When we first lay eyes on Johnny Moynihan, he is seemingly alone in a large, cluttered house, preparing to receive trick-or-treaters. But, in a sensitive and engrossing performance from Gordon Clapp, something is clearly wrong. A permanent frown mars Johnny’s face, and his bulky, shuffling body seems to slowly be crushing in on itself. When his daughter, Claire (Jenni Putney), comes to call, we get a hint of Johnny’s New England accent—“Park the car,” he tells her—and an inkling of his woes. His wife, Nancy (Kathy Manfre), a victim of early onset Alzheimer’s, has reached the stage of the disease where he can no longer properly look out for her.

As Johnny describes to Claire what he has been through in dealing with Nancy over the course of the day, it might seem that the viewer has been trapped in a very depressing play about a devastating illness. But, as Johnny divulges just how he treated his dear wife in the wake of being freaked out by her behavior, it becomes clear that he is not so kindly, even though he always hands out the full-sized candy bars to the neighborhood kids, and that Neary has more on his mind than just compassionate care.

Soon Johnny’s son, Teddy (David Mason), arrives and hears of his mother’s condition. The family tensions grow palpable as we learn that Teddy is in line to become the police chief of their small town, a position once held by Johnny’s father but which Johnny never achieved. Teddy, however, has a history of violence, and Claire’s husband, an editorialist for the local paper, is out to keep him from getting the promotion. As if the tension between the three were not heated enough, nosy neighbor Hannah (Kathy McCafferty) keeps dropping by to act as a catalyst for a series of blow-ups. That she is an ex-girlfriend of Teddy’s makes matters no less volatile. By the time all the domestic matters have been sorted out, with previously undisclosed allegiances revealed and exit strategies put into place, Johnny is left virtually alone to wallow in the tragic consequences of his decisions. His world view of what it means to honor and to keep, in sickness and in health, is radically altered.

“Hints of betrayal, mental illness and physical violence pervade the air, so don’t even ask what happened in the basement.”

Clapp’s powerhouse execution of a father with all the wrong dreams receives strong support from his co-stars. Though we know a lot about Teddy before he even enters, Mason’s flying off the handle and reaching for serenity make for an explosive mix. Putney, meanwhile, supplies the right blend of compassion and disgust as the beleaguered Claire, and McCafferty makes Hannah a believable interloper, unable to stay away even as things get worse every time she drops in.

Director Carol Dunne brings a masterly pacing to the proceedings, pulling focus toward important clues while navigating the audience through a patchwork of lies. Among the clutter of scenic designer Michael Ganio’s well-worn living room are baskets of toys that may be there for Johnny’s grandkids or for a much sadder reason. Meanwhile, a jack-o’-lantern, bearing a demonic smile, looks on approvingly from atop a bookshelf.

Trick or Treat runs through Feb. 24 at 59E59 Theaters (59 E. 59th St., between Park and Madison avenues). Evening performances are at 7 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday; matinees are at 2 p.m. Saturday and Sunday. To purchase tickets, call the box office at (646) 892-7999 or visit www.59e59.org.

Blue Ridge

Last year, in one of the most exciting Off-Broadway debuts of the season, the Ensemble Studio Theatre staged Abby Rosebrock’s Dido of Idaho, a darkly comic manifesto on feminism in the face of infidelity, and morals in the face of family dysfunction. Rosebrock has now returned with another new work, a character-driven drama called Blue Ridge, presented by the Atlantic Theater Company.

As with Dido, a cheating man and the effect he has on the friendship between two women is at the center of the play’s emancipatory storyline, and both works share an affinity for Tennessee Williams references as well as a certain skepticism when it comes to southern U.S. Christianity. Even if Blue Ridge is lacking the razor-sharp wit and stunning surprises of Dido, Rosebrock nonetheless succeeds in creating six well-rounded characters with believable flaws and inescapable fates. There are few explosions to be found here, but the simmering tensions brought to bear by a strong ensemble of actors under the tight direction of Taibi Magar provide a satisfying status quo; they are a happy indication of the playwright’s continuing growth.

Chris Stack, as Hern, and Kristolyn Lloyd, as Cherie, share an intimate moment in Abby Rosebrock’s Blue Ridge. Top: Alison (Marin Ireland) and Cole (Peter Mark Kendale) work on their issues.

Set primarily in the living room of a Christian halfway house in North Carolina, Blue Ridge opens on Bible Study Wednesday. The home’s newest resident, Alison (Marin Ireland), is struggling to fit in. Fidgety and more familiar with the writings of Carrie Underwood than those of the Apostles, her manic way with words brings an uncomfortable energy to the group. It is also an outward sign of her anger issues. A high school English teacher who took an ax to her principal’s car after an emotional entanglement, Alison is in a constant state of flux between being humorously energetic and dangerous to herself and those around her.

As the story progresses from November to Christmas Day, Alison and her “intermittent explosive disorder” build and destroy relationships with her overseers as well as with her “inmate” colleagues. These include Cherie (Kristolyn Lloyd), a fellow teacher who is there voluntarily to work through her addiction issues; Wade (Kyle Beltran), a guitar-strumming voice of reason making his way through the 12-step program; Cole (Peter Mark Kendale), a deep-thinking Army vet whose previous residence was a psychiatric institute; Pastor Hern (Chris Stack), their religious leader with intimacy issues of his own; and Grace (Nicole Lewis), the optimistic and overstretched manager of the home.

Wade (Kyle Beltran), plays for Cherie (Lloyd). Photographs by Ahron R. Foster.

With this boisterous performance, Ireland seals her position as Off-Broadway’s foremost portrayer of put-upon, lower-middle-class Caucasian women. From her slaughterhouse job in Kill Floor (2015, Lincoln Center Theatre) to her role as a Polish immigrant housekeeper in Ironbound (2016, Rattlestick Theater) to her excellent interpretation of a traumatized professor and single mother in On the Exhale (2017, Roundabout Underground), men have tried to break her characters in nearly every way imaginable. This time, damaged already from her relationship with her boss, Alison is triggered by Pastor Hern and his proclivities. The collateral damage includes the end of her friendship with Cherie, emotional tumult with Wade and physical aggression with Cole. Rosebrock’s neat trick here is that none of these characters is actually villainous. Each moves forward with only the best intentions, but they are ultimately undone by their mental, emotional and spiritual frailties. Kendale brings a riveting stoic minimalism mixed with an odd playfulness to Cole. Beltran’s outward calm betrays just enough of Wade’s internal struggles. And Lloyd’s Cherie, trusting and then betrayed, is rendered at just the right temperature. She also provides the ultimate dialect-infused observation in the work’s examination of sex and consent:

Not only does no always mean no, but.

Sometimes yes means juss means, I'm only doin this cause I fill like you'll leave me er cheat on me if I don't--

Cause iss not safe out there, y'all's hillbilly asses runnin around, I don't wanna be single again, / so--

I guess I consent to this act, but.

S'not cause yer special.

Scenic designer Adam Rigg’s spacious living area, set in front of a row of towering Carolina pine trees, seems too pristine and stain-free for a sanctuary that sees so much physical and emotional traffic, although, as Alison points out, “the Yelp review said best in Southern Appalachia.” The production’s final scene takes place in a high school, but Rigg offers no effort here beyond pushing the furniture to the side and throwing some plastic chairs into the middle of the room. Perhaps that’s what a New York playwright gets for adding a completely new locale in the last seven pages of the script, but the audience shouldn’t have to suffer the results.

Blue Ridge plays through Jan. 26 at the Atlantic Theater, 336 W. 20th St. Performances are at 7 p.m. on Sunday and Tuesday, and 8 p.m. Wednesday through Saturday; matinees are at 2 p.m. Saturday and Sunday. For more information and to purchase tickets, call (866) 811-4111 or visit atlantictheater.org/blue-ridge.

Christmas in Hell

Like the despised fruitcake that is passed from one generation to the next in Gary Apple’s hard-to-digest musical, Christmas in Hell, the show itself is an amalgam of strange ingredients. Sometimes sincere, usually madcap, but hardly ever having to do with Christmas, it is the tale of an 8-year-old boy mistakenly sent to Hades and the father who has to drink some Clamato to get him back. With one song that rhymes “Jesus” with “Chuck E. Cheese’s,” and another composed almost entirely of variations of the F-word, some in the audience may find the show in bad taste. With references to Charles Manson and Leona Helmsley, others may simply find it stale.

Downstairs

As the novelist Joseph Heller observed, “Just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean they aren’t after you.” And as the three characters who barely survive Theresa Rebeck’s twisting and twisted thriller, Downstairs, demonstrate, paranoia is merely one indication that someone you know could be harboring bad intentions. Other warning signs include psychopathic tendencies, the inability to separate reality and fantasy, and sheer, anesthetizing dread. Maybe your workmates are dispensing poison, or your husband is not the man you thought you knew, or your sister has had enough. Maybe that pipe wrench would be an effective blunt instrument. Or, maybe it’s just all in your head. Rebeck and her stellar cast keep us guessing through a tense, intermission-less hour and 45 minutes, while simultaneously pondering larger questions involving inheritances of both the genetic and financial variety.

John Procaccino plays Gerry, the controlling husband of Irene in Theresa Rebeck’s Downstairs. Top: Real siblings Tyne Daly and Tim Daly are Irene and Teddy, the sister and brother in Rebeck’s thrilling family drama.

Basements are notoriously the dark room where the bodies are buried, but Rebeck flips the script from the start. With a comfy couch, a coffee-making machine, and a ray of light coming in from a street level window, the downstairs is the only secure space to be had in the house of Irene and Gerry (Tyne Daly and John Procaccino). Finding safety there is Irene’s brother, Teddy (Tyne’s real-life brother, Tim Daly). He is in lost-boy mode, a grown adult wandering the room in his underpants with a glazed expression on his face. He’s had a tough time of late, but just how reliable are his tales of woe and plans for redemption? Given his stinginess with details and his shaky grasp of reality, chances are he is just plain desperate.

None of this is lost on Irene, who genuinely cares about her sibling, fortifying him with this sanctuary as well as with hot meals and desserts from their youth. Their interactions reveal an ominous family history involving an absent father and a cruel, alcoholic mother who left Irene a cash windfall and bequeathed Teddy nothing other than an unstable mind.

Irene, meanwhile, has her own dilemma. Her husband has, over the years, broken her to the point where she has become a hostage in her own home. Her talks with Teddy reveal that Gerry has taken over the finances, denied her the chance to have children and generally terrorized her into submission. The audience first encounters him at the same time Teddy does. With Irene out shopping (at least, we hope she is out shopping and not, perhaps, stuffed in an upstairs closet), the man of the house comes down to give Teddy his marching orders. He is a big guy with a creepy calmness who cannot quite sell the story that it is Irene who really wants him gone. The second time we encounter Gerry, Teddy has indeed made a departure but not before leaving Irene with information she can use to free herself from her living hell. In a wonderfully dark resolution between husband and wife, Gerry goes full psycho, uttering menacing lines like, “You found rat poison in the basement? Maybe I was killing rats.” Irene, though, holds the upper hand, and it is clenching that pipe wrench.

“Warning signs include psychopathic tendencies, the inability to separate reality and fantasy, and sheer, anesthetizing dread.”

Despite such theatrics, Rebeck avoids melodrama and endows her work with patches of poetry. For instance, reflecting on the mechanics of human nature, Irene observes, “There’s that funny thing they say, that all your cells die every seven years. ... You’re a new person, every seven years. So since then, since we were kids, we’ve been new people how many times?” Director Adrienne Campbell-Holt knows when to be subtle and when to be harsh, exploiting the seeds of doubt that, despite what the audience knows to be true, never quite go away. Is Gerry really a madman, or a reasonable fellow with an unstable wife? How is Teddy sure of his sister’s predicament while barely understanding his own? Is Irene a victim of abuse, or does insanity run deep in the family? Late in the play, Teddy is passed out on the couch, and the odds are fifty-fifty that he is either in a happy slumber, or stone-cold dead.

Teddy (Daly) makes an unsavory discovery. Photographs by James Leynse.

Mr. Daly skillfully walks the line between victim and savior. Ms. Daly, returning to the Cherry Lane, where her theater career began in 1966, pulls off the admirable feat of bringing depth to a character who has been beaten numb. And Procaccino is bone-chilling, chewing the scenery when called for, demonic when up against the wall. Among the many clever touches in the scenic design by Narelle Sissons, the smartest is the landing near the top of the staircase that leads from the unseen upstairs down to the basement. It serves as a beacon. When we spy Gerry, visible from the waist down, pausing there, the tension mounts. When a pair of female legs come into view, there is a palpable sigh of relief that Irene is still on her feet.

Theresa Rebeck’s Downstairs runs through Dec. 22 at the Cherry Lane Theatre (38 Commerce St.) on a schedule as twisted as its plot. Evening performances are at 8 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday, with an additional performance at 8 p.m. Dec. 2 but none on Dec. 20. Matinees are at 2 p.m. Wednesday and Saturday and 3 p.m. Sunday but there are no matinees on Nov. 28 or 30, or on Dec. 12. For ticket and information, call (212) 352-3101 or visit primarystages.org.

Lewiston/Clarkston

Low-wage workplaces in two towns separated by a river provide the backdrop for Lewiston/Clarkston, two 90-minute dramas separated by a meal break. Playwright Samuel D. Hunter peppers these compelling plays with characters who are descendants of 19th-century explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. But their reasons for traveling, or staking territorial claims, have more to do with personal setbacks and family tragedy than with discovery or affirmation. If Lewis and Clark were dispatched westward by Thomas Jefferson, these beaten-down distant relatives, making their way through a drug-addled world of subdivisions and superstores, seem as if they were sent on the road by Jack Kerouac.

Chris (Edmund Donovan) and Heidi Armbruster as his mother, Trisha. Top: Arnie Burton plays Connor, the platonic roommate of Kristin Griffith’s Alice, in Lewiston, the first half of Samuel D. Hunter’s linked plays, Lewiston/Clarkston.

Lewiston, the more intriguing of the two works, is set at a fireworks stand off a rural highway in Lewiston, Idaho. Alice (Kristin Griffith), a sturdy and stoic septuagenarian, runs the place while holding tight to the 20 acres of family land that have yet to be overrun by new construction. Alice’s helper, platonic roommate and voice of reason is Connor (Arnie Burton), a former butcher who just wishes that Alice would sell off her property so they could go live in a nice condo with a swimming pool. Hunter keenly shows the pair to be stuck in an unnatural stasis. Field mice, shaken by the shrinking fields, have taken to gnawing through the stand’s inventory to eat the gunpowder, while the only fireworks Alice can legally sell are those that stay tethered to the ground. “Fountains, sparklers, smoke bombs, little rolly things. Not much else.” But then Alice’s 24-year-old granddaughter, Marnie (Leah Karpel), comes to call, providing the spark that will blow up their unstable calm.

It is Marnie’s first visit since she was a child, and although she arrives with just a backpack, she brings no shortage of emotional baggage. She and Alice are both haunted by Marnie’s mother, who arrives as a disenfranchised voice on a collection of cassette tapes that Marnie has inherited. Marnie’s connection to the land, meanwhile, is full of ironies. Her childhood home is now a gas station. She has built, and abandoned, an urban farm in Seattle. The very concept of urban farming sounds crazy to Connor, but not as crazy as her vegetarian lifestyle. “Oh well lah dee dah, look who’s too good for the food chain,” he says mockingly. All three characters get under one another’s skin as they weigh the importance of holding on to the past against the sacrifices of letting it go. Precise, charismatic performances from Griffith and Burton, as survivors who have had to swallow a lot over their lifetimes stand in juxtaposition to Karpel’s sensitive work as a woman whose own problems are just beginning. Under the fine direction of Davis McCallum, the trio brings a perfect tension to the proceedings.

“If Lewis and Clark were dispatched westward by Thomas Jefferson, these beaten-down distant relatives, making their way through a drug-addled world of subdivisions and superstores, seem as if they were sent on the road by Jack Kerouac.”

Where Lewiston is about finding home, Clarkston is about fleeing it. Where Lewiston slowly peels back layers of story to reveal harsh realities, Clarkston tears open its wounds and lets them seep. The action, this time, takes place in Clarkston, Wash., under the cold, fluorescent lights of a Costco, that great American icon of overabundance amid poverty, with its shelves full of 80-inch televisions and giant tubs of cheese puffs.

Two night-shift workers, Chris and Jake (Edmund Donovan and Noah Robbins), are getting to know each other. There are commonalities. They are both in their early 20s, both have fled their families, and both are gay. But the tensions lie in their differences. Chris is outwardly rugged yet sensitive enough to want to be a writer. He has been living on his own for six months, needing to escape his mother, Trisha (Heidi Armbruster) and her struggles with drug addiction. Jake is scrawny and sickly, carrying a disease that he is sure will kill him before he turns 30. He has escaped his apparently caring and well-to-do family in Connecticut, because it is the only thing in his life that he can escape. Chris plans for the future while Jake sulks: “It’s a terrible time to be alive. There’s just nothing left to discover.”

Noah Robbins, foreground, as Jake, and Donovan as Chris in Clarkston. Photographs by Jeremy Daniel.

Gut punches come hard and fast to Chris. His dream is crushed, his mother falters, and he learns a hard truth about his absent father. Jake provides little solace as they attempt to become more than just friends. He considers suicide in front of Chris one moment and further aggravates Chris and Trisha’s broken relationship the next.

Hunter is perhaps counting on Jake’s sickness to make him a sympathetic character, but despite (or perhaps because of) a performance from Robbins that captures all of Jake’s irritating qualities, he is difficult to like. Chris is in need of comforting, but it is hard to buy the attraction he feels. We are left wanting more interaction between Donovan and Armbruster, who are no less than captivating in the scenes that they do have together. Hunter is also too carefree, at times, in his setups. We learn, early on, that Jake tends to drop things and that neither man has ever been to the Pacific Ocean, so we know it is only a matter of time before Jake indeed drops something important and the two make a beeline for the coast.

McCallum and his production team keep things intimate, staging the plays for an audience of 51 in what was formerly the house of the Rattlestick Playwrights Theater. Folding chairs on a carpeted playing area have replaced the battered old installed seating, and communal tables come out between plays, allowing the audience to compare appetites while contrasting the West Village to the West.

Lewiston/Clarkston is playing through Dec. 16 at the Rattlestick Playwrights Theater (224 Waverly Place). Evening performances are at 7 p.m. Monday and Wednesday through Saturday; matinees are at 3 p.m. Sunday, with special Friday matinees at 1 p.m. on Nov. 9, 16, and 30. For tickets and information, visit rattlestick.org.

The Evolution of Mann

Despite the title, the lead character in The Evolution of Mann, a busy and lovelorn new musical from Douglas J. Cohen and Dan Elish, does not rise to a higher plane of existence. Rather than evolve, Henry Mann, played with his broken heart on his sleeve by Max Crumm, falls victim to his own choices as well as to the whims of those he matrimonially pursues. If, over the course of 90 minutes and a dozen songs, he ultimately finds a ray of hope, it is the females around him who elevate his consciousness, if not his likability.

Spin Off

Bernard Pomerance, who died last year at age 76, is best known for having written that brutal little lesson in humanity, The Elephant Man. That play’s best line, “We have polished him like a mirror, and shout hallelujah when he reflects us to the inch,” nicely encapsulates the playwright’s concerns over the societal tendency to perform acts of charity for the sake of the giver. But, as is discovered in the wandering world premiere of Spin Off, which was drafted in 2003 and revised in 2006, Pomerance’s thought processes were not always so tidy.

The Revolving Cycles Truly and Steadily Roll’d

A teenage boy goes missing, and his foster sister embarks on an urban odyssey to track him down in the Playwrights Realm’s brazen production of The Revolving Cycles Truly and Steadily Roll'd. Early-career dramatist Jonathan Payne unleashes a Pandora’s box of theatrical devices, including symbolically named characters, direct audience interaction, screen projections, a live-streaming cellphone, and actors not only breaking the fourth wall but breaking character as well. Veteran off-Broadway director Awoye Timpo molds it all into a bracing panorama of societal failures amid institutional racism. That is, until the final scene when, with the play’s momentum waning, she and Payne risk one last gambit that unfortunately swallows up all that came before it.

Summer Shorts 2018 (Series B)

The inherent tensions of sibling rivalry, a father and son reunion and a budding office romance drive the three 30-minute plays that make up the uneven Series B of this year’s Summer Shorts festival, presented by Throughline Artists. And, perhaps unintentionally, this showcase of new American one-acts is also a lesson in how the invention of the smartphone has changed the craft of playwriting.

Scissoring

Scissoring takes place in present-day New Orleans, and even though several ghostly spirits make appearances in Christina Quintana’s thoughtful new one-act, it is modern Catholicism and not voodoo that haunts the play’s protagonist, Abigail Bauer. Free of any Southern stereotypes, the work has a sensibility that is not only post-Katrina, it is decidedly post-Blanche. Abigail might be suffering from delusions, but she has no need for brutish men nor the kindness of strangers. Instead, she is empowered by the women she knows and made strong by the tough kindness of her lover and her colleague, before gaining the wherewithal to be kind to herself.

Secret Life of Humans

Like the Scottish-American songwriter with the same name, British playwright David Byrne is concerned with life during wartime, and captivated by one of life’s great questions: “Well, how did I get here?” In this coolly cerebral and beautifully staged production of Secret Life of Humans, Byrne, who codirects with Kate Stanley, transports us through the present day, the 1940s and the 1970s, with pit stops at the dawn of humanity. He explores a one-night stand, a marriage abruptly ended and, of all things, the darkly ironic and secretive career path of real-life mathematician Jacob Bronowski. As fuel for the fire, Byrne pulls big ideas from historian Yuval Harari’s bestseller, Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, as well as Bronowski’s 1973 BBC series, The Ascent of Man.

It Came From Beyond

Like a comet in an irregular orbit, It Came From Beyond has returned to menace Manhattan, bearing down on Off-Broadway while emanating just enough charm and good will to keep from crashing. This sci-fi musical was spawned in 2005 at the New York Musical Festival, then rose again the next year in Los Angeles. Now, back for an oddball run of Tuesday-only performances, it turns out that, despite the threatening title, it has come in peace. And that’s the problem. Meant as an homage to the 1950s and as a parody of that era’s Cold War monster flicks (most obviously, It Came From Outer Space), playwright Cornell Christianson’s script is campy, but not sufficiently outrageous; other-worldly, but not scary. And opportunities to freshen the writing to reflect current political and societal upheaval have gone untaken.

The Edge of Our Bodies

A 16-year-old prep school student takes a train to New York City, spends some time in a bar, encounters odd sexual shenanigans in a hotel room, and struggles with an assortment of inner conflicts. In 1951, J. D. Salinger turned this scenario into gold with The Catcher in the Rye. But, in the TUTA Theater Company’s abstract and lumbering production of a 2011 play by Adam Rapp, these same elements hold little value. With extensive doses of narration broken only by a few unexplainable affronts of noise and light, The Edge of Our Bodies shares a border with the limits of our patience.

Dido of Idaho

Abby Rosebrock is a different kind of triple threat. As a playwright, she brings an invigorating new voice to the stage with the debut of her comedy-drama Dido of Idaho, at the Ensemble Studio Theatre. As an actor in her own play, portraying a former beauty pageant contestant in crisis, her comic timing is precise. And as a practitioner of stage combat, “threat” is too gentle a word for her character who, when faced with a challenge to her domestic security, brandishes a razor-sharp pair of cuticle scissors.

Three Wise Guys

Forming a theater company is a bold move; ending a successful one is even bolder. A hat tip, then, to Scott Alan Evans, a founding member of TACT (The Actors Company Theatre) who, over the past quarter century, has produced and/or directed more than 150 productions for the company. Having declared the troupe’s artistic mission accomplished, Evans takes a final bow with an uneven production of a new work, Three Wise Guys, which he not only directs, but also co-wrote, with screenwriter and occasional lyricist Jeffrey Couchman.

Is God Is

The Soho Rep had been staging vital productions out of its small Walker Street theater in Tribeca for a quarter century when it was discovered, in 2016, that the company had been in violation of an occupancy limit of 70 people. Through a combination of fund-raising and city agency support, the company has now returned to its home space, which includes a new fire-safety system. It is a fitting improvement, because flames are the essential metaphor of Aleshea Harris’s explosive Is God Is. In this allegorical tale of vengeance and family honor, twin sisters, burned both literally and figuratively, create an inferno that swallows nearly everyone they meet.

A Kind Shot

In basketball, as Terri Mateer instructs in her solo show, a kind shot is one that touches nothing but net. No bouncing off the backboard, no clanging around the rim, just a sphere on a pristine trajectory that ends with a satisfying swish. Basketball was an integral part of Mateer’s high school, college, and young adult years, but the arc of her life was anything but clean. In an extended monologue that at times devolves into a bull session with the audience, then pivots into entertaining b-ball play-by-play, she recounts how the loss of her father gave way to a series of mentors, some wanting to help her, others wanting to help themselves to her. Though the dialogue could stand some tightening, and a director could help Mateer better realize the moments that call out for a pause, her saga, her stage presence and her intimate style of delivery bring home a win. The fact that her story is also one of outracing relentless sexual harassment, shows that her cultural timing is as strong as the pass timing of her youth.