Riley (Sophia Lillis, left) and Alex (Justin H. Min, right) tell Maneesh (Karan Brar) about the government contract that the tech company Athena hopes to land, in Matthew Libby’s Data.

With Data, playwright Matthew Libby has crafted both a techno-thriller and an indictment of Big Tech, in all its mercenariness and disregard for personal privacy and security. Whereas tech-themed dramas typically portray futuristic scenarios, Data’s story of a Silicon Valley company aiding in a federal immigration crackdown seems ripped from this week’s headlines.

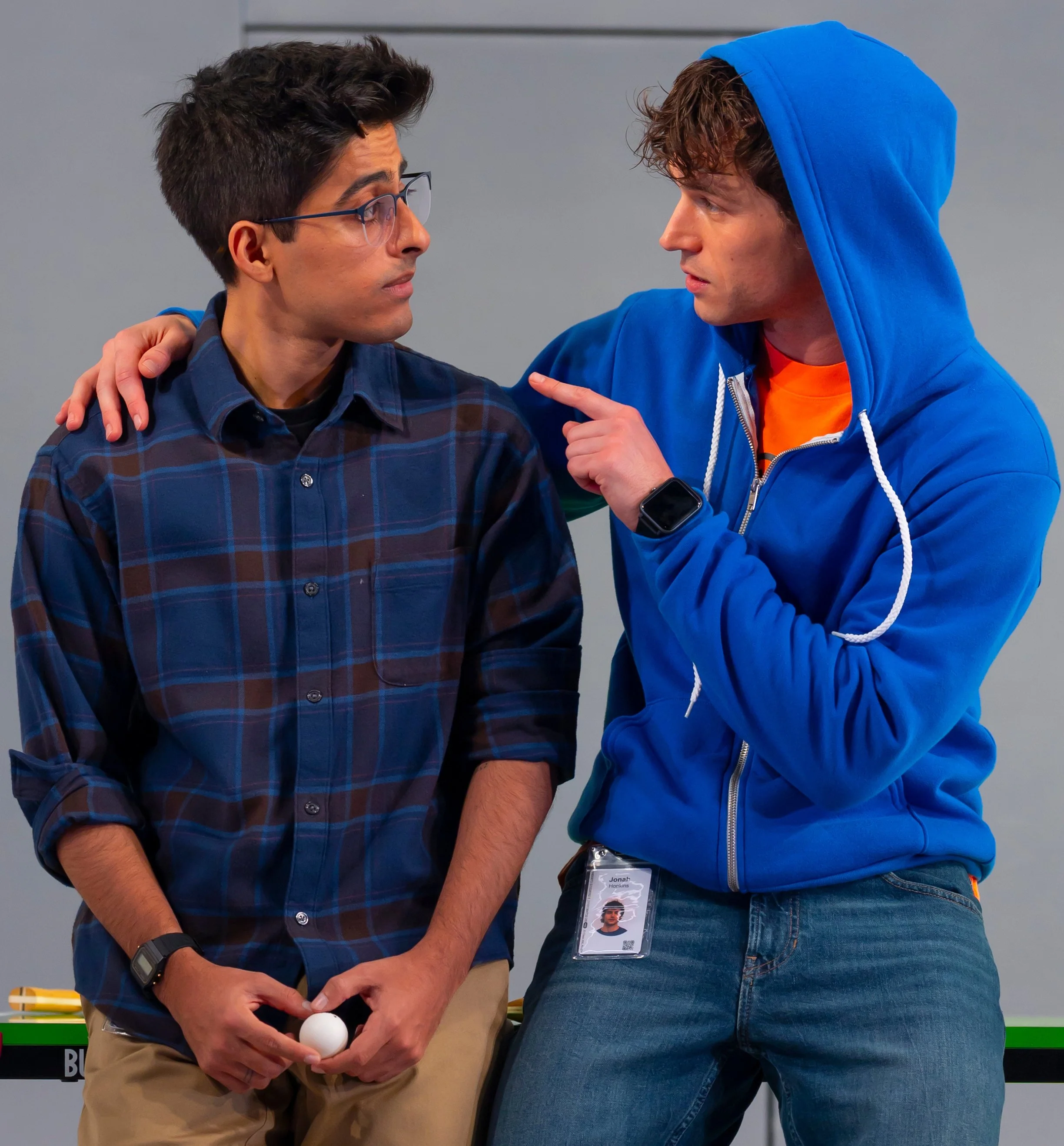

Maneesh and his designated Athena mentor, Jonah (Brandon Flynn), take a break after a playing Ping-Pong. Photographs by T. Charles Erickson.

Data premiered regionally last fall, and Libby has said he began writing it in 2018, but the software under development in the play sounds a lot like an initiative of the current Trump administration: it would comb a visa applicant’s digital footprint to “make a determination whether said applicant will be a positive and productive addition to America and its values.” And the Department of Homeland Security officials who put out the contract bid have a Trumpian level of transparency: “They refuse to elaborate on exactly which attributes the software should evaluate,” one of Data’s programmers notes, and they want “to implement it before anyone notices.”

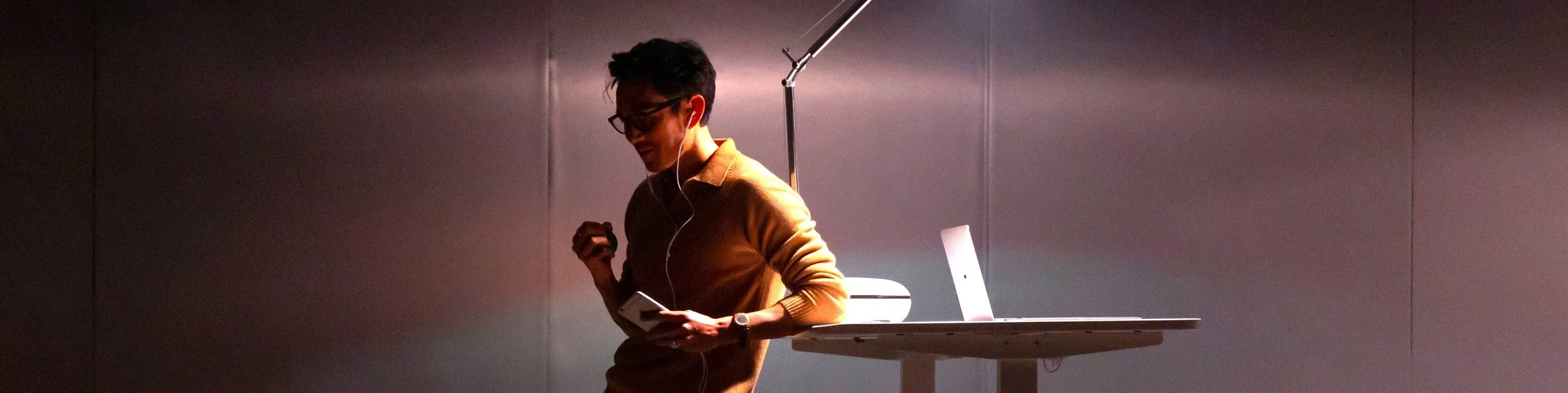

All four characters in Data are employed by data-mining giant Athena, and the play takes place at its offices. The most recent hire is Maneesh (Karan Brar), just a few months out of college and a member of the user experience team. There, he works alongside the gung-ho but less talented Jonah (Brandon Flynn), who’s in his fourth year with Athena. Jonah is as enthusiastic about the corporate culture—always attending the Taco Tuesday hangs, idol-worshipping the higher-ups—as Maneesh seems wary of it. His older brother, Karthik, was an Athena employee at the time of his accidental death, and Maneesh has followed Karthik to Athena mostly to please their parents.

Riley (Sophia Lillis), Maneesh’s college classmate and an Athena data analytics engineer, runs into him in the break room one day, unaware he has joined the company. She knows that this fellow alum of their college program’s honors cohort has the chops for data analytics, the most coveted placement at Athena, and tips off department head Alex (Justin H. Min) about Maneesh’s skills—in particular, the algorithm he created for his senior thesis to predict “rare events.” Invited to join data analytics, Maneesh is stunned when he hears about the Homeland Security project. “It allows the government to define parameters of what’s good and what’s bad,” he says. “Doesn’t it have the potential to be really, really dangerously misused?”

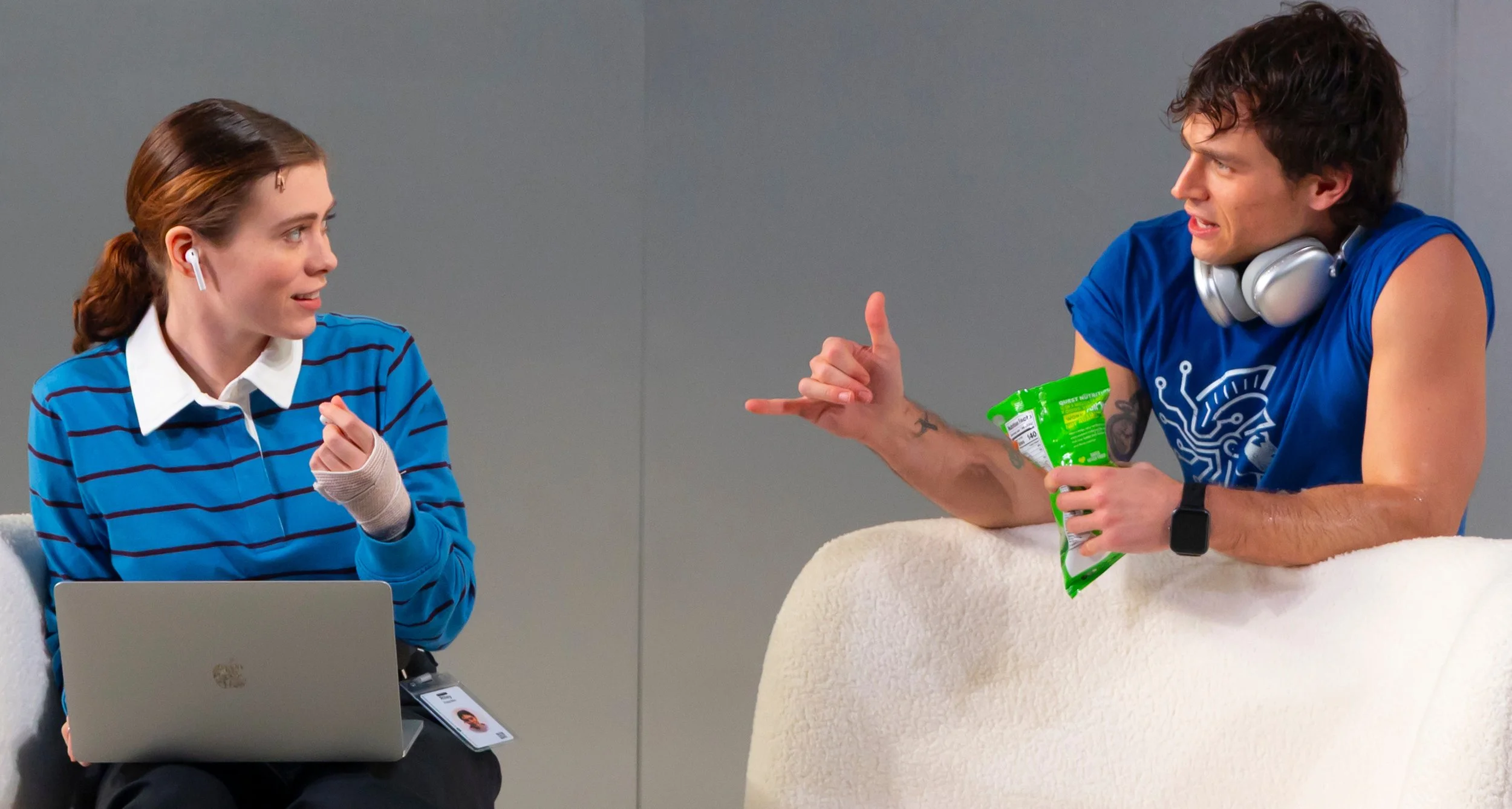

“If I get hit on one more time by some entitled tech bro,” complains a frustrated Riley, as Jonah does just that.

Like the smooth-talking corporate climber he is, Alex claims the work is noble in consequence: “Using data to find insights, make sense of the world, beyond the human eye … we’re the hidden artillery that’s going to shape the future. We’re the fighters protecting democracy.”

Riley sees it differently. “It’s going to codify policy—bigoted policy—behind a veil of mathematical objectivity,” she says. Frazzled and ultra-anxious, Riley makes the play’s most provocative allegation about Big Tech: “I come here every day, and I make the world a worse place.”

These differing perspectives on technology’s impact on society—along with the suspense around Maneesh’s copyrighted algorithm, his participation in the government contract and the possible leaking about that top-secret project to the press—fuel the drama in Data. The play also offers a penetrative look at the industry: how it has changed since the pioneering days of the early 2000s (more competition, less money); how it hasn’t (still sexist!); how the changes leave employees fearful of “streamlining” (layoffs, that is); how companies use purportedly morale-boosting mantras, like “Proximity to important work is itself important work,” to encourage subservience in the workforce; and how so many perfectly mediocre bro types, like Jonah, manage to advance.

Riley may have reached her moral breaking point at Athena.

While theatergoers should be engrossed by midpoint of the 100-minute drama, they may not take to Data immediately—unless they’re comfortable with, or intrigued by, conversation about “real-time CEP analysis,” “gen-AI coding agent,” “react frameworks,” “MLflow with good tooling” and other such jargon. The first few scenes can be talky, maybe a bit tedious.

But once Maneesh has learned about the software he’s expected to create, the tension and mystery continually ramp up, fed in part by the superb performances of Lillis and Brar, who make Riley’s panic and exasperation and Maneesh’s inner turmoil and outward reticence thoroughly convincing. Flynn and Min are spot-on as well, albeit in less emotional roles, and Brar’s and Flynn’s roles require extended Ping-Pong playing simultaneous with conversation in several scenes.

Data set designer Marsha Ginsberg has fashioned the stage as an off-white box. It is framed by chasing lights during the between-scene blackouts—the audience never sees furniture being moved—which are soundtracked with bursts of electronic music (by sound designer Daniel Kluger). Despite these sci-fi-like trappings, Data couldn’t feel more timely and real.

Data runs through March 29 at the Lucille Lortel Theatre (121 Christopher St.). Performances are at 7:30 p.m. Tuesday through Sunday, with matinees at 3 p.m. Saturday and Sunday. For tickets and more information, visit boxoffice.lortel.org.

Playwright: Matthew Libby

Director: Tyne Rafaeli

Sets: Marsha Ginsberg

Costumes: Enver Chakartash

Lighting: Amith Chandrashaker

Sound & Original Music: Daniel Kluger