Kelley Curran as Mina Harker (left) and Matthew Saldivar as Doctor Steward in Kate Hamil’s Dracula.

In Kate Hamill’s adaption of Bram Stoker’s Dracula at Classic Stage Company, fighting against vampires becomes synonymous with fighting the patriarchy. With Sarna Lapine directing (she also directed Hamill’s Little Women) and a stellar cast, Hamill’s Dracula manages to be hilarious without descending into farce, perhaps because so much of the humor is in the service of a feminist reshaping of Stoker’s novel, which turns the struggle against vampires into a struggle for self-individuation and self-determination.

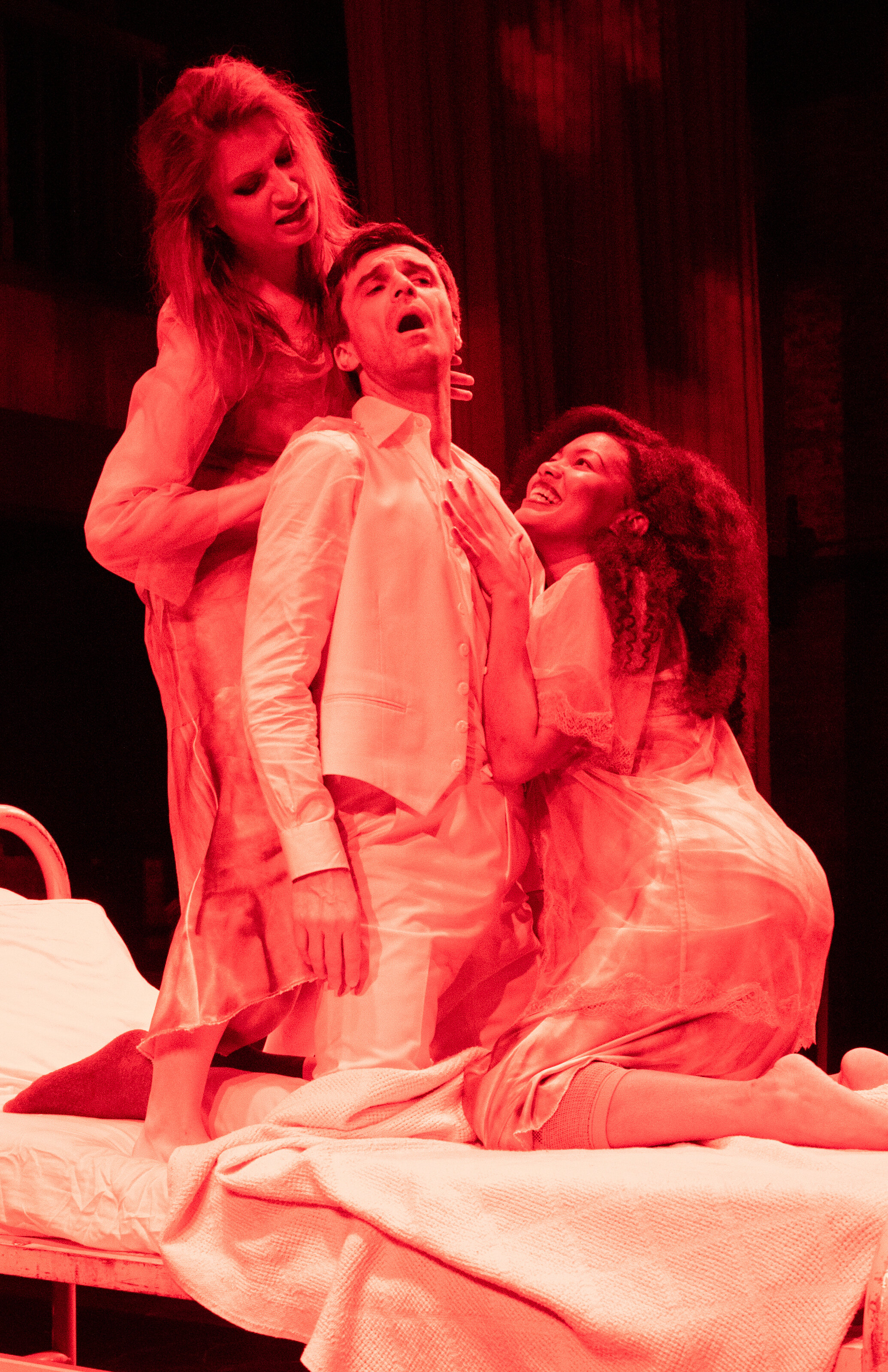

Count Dracula’s wives—Drusilla (Laura Baranik, left) and Marilla (Lori Laing, right)—prepare to feed on Jonathan Harker (Michael Crane, center).

The story and characters loosely follow Stoker’s novel. The English solicitor Jonathan Harker (Michael Crane) leaves behind his pregnant wife Mina (Kelley Curran) in order to go to Transylvania, to the castle of Count Dracula (Matthew Amendt), to complete a real-estate transaction. Harker can’t even fathom the concept of having his wife accompany him on such a trip: “And write to me every day,” Mina says, “and tell me of your adventures—since I cannot have them.”

Dracula, played with flamboyant, wicked glee by Amendt, and his wives (Laura Baranik and Lori Laing, who also take on other roles), set upon Harker and plan to move their deadly presence to England. Back in the English seaside town of Whitby, Mina is with her friend Lucy (Jamie Ann Romero), whose betrothed, Doctor Seward (Matthew Saldivar), runs an asylum that houses among its residents one Renfield (Hamill), a Dracula superfan and his would-be servant. In brief interactions, Curran and Romero bring out the deep bond between Mina and Lucy, as their conversation alternates between teasing wordplay and discussions of the limitations of a woman’s life in marriage. Lucy is unsure of her choice of Seward:

I have no family, and while I am comfortable enough—without a husband, I have no future, no prospects; I cannot even dictate how my money is spent, it’s all held in trust. But our whole destinies are wrapped up in the men we marry; once we are wed we are—little better than their chattel, according to the law, and I just—wish I could be absolutely sure of his character.

Indeed, after Lucy is dead at the hands of Dracula, Mina will remind Seward, who is intent on remembering her as an “angel,” that “Lucy was vulgar—and funny—and clever—and complicated—she was not some porcelain idol for you to worship!”

Doctor Seward is meant to embody Victorian mores, particularly regarding gender differences: “Tends to mansplain,” as the character notes put it. He’s played with wonderful, over-the-top self-seriousness and confidence by Saldivar, who nails some of the biggest laugh lines of the play and manages to make Seward ridiculous but ultimately transformed by his experiences of female leadership.

Doctor Van Helsing (Jessica Frances Dukes, right) tends to Lucy Westenra (Jamie Ann Romero, center), as Mina looks on. Photographs by James Leynse.

That leadership comes in the unexpectedly female presence of Dr. Van Helsing (Jessica Frances Dukes), a vampire hunter who wears a cowboy hat and has a long scar on her face and who “takes no crap from anybody.” She is the only character, other than Renfield, who wears gray rags that might once have been a straitjacket, not clad in all white in Robert Perdziola’s costume design. Van Helsing—who must remind Seward and others that she is Doctor and not Madame—not only diagnoses Lucy, who has been bitten by Dracula, and informs the incredulous others of vampires, but also serves as a coach of sorts for Mina, reminding her that women have agency and that her pregnancy (or her “condition,” as the men call it) is not an obstacle: “That doesn’t stop your brain, does it? God knows, it shouldn’t stop your life.”

As the fight against the vampires proceeds, the language in which it is described becomes less literal and the figure of Dracula takes on the qualities of masculine oppression or violence writ large. This culminates in the play’s chilling conclusion, when Mina can no longer be certain of her husband, even though he has ostensibly recovered from his vampiric infection. To be a fighter like Van Helsing may be the only option.

One of the accomplishments of Lapine’s direction is that she doesn’t let the comedy overwhelm the eeriness or excitement of the play—it is not a parody but could easily have seemed so in less sure hands. Hamill’s adaptation perfectly aligns with Classic Stage Company’s mission of “reimagining classic stories” in ways that speak to modern audiences. Perhaps the themes are hammered home a bit too obviously or repetitively—nonetheless, Dracula is a fun theatrical event, with a positive message but an ending that suggests the struggle is ongoing.

Dracula plays through March 8 on an irregular schedule at Classic Stage Company (136 East 13th St.), in repertory with Frankenstein. For tickets and information, call (212) 677-4210 or visit www.classicstage.org .