Craig Bierko (left) portrays Alan Townsend, son of the title character, played by Len Cariou, in Harry Townsend’s Last Stand.

Toward the end of Harry Townsend’s Last Stand, a play that’s set in a New England lake house and revolves around the strained relationship between an aging father and his adult child, a door is opened and the call of a loon is heard. It immediately brings to mind On Golden Pond (“The loons, Norman!”), a play that’s set in a New England lake house and revolves around the strained relationship between an aging father and his adult child. This association doesn’t do Harry Townsend any favors, though, since its parent-child relationship is not as well developed as the one in On Golden Pond and, consequently, the conflict and emotions feel forced.

Harry Townsend and his son, Alan, have a serious talk in George Eastman’s play.

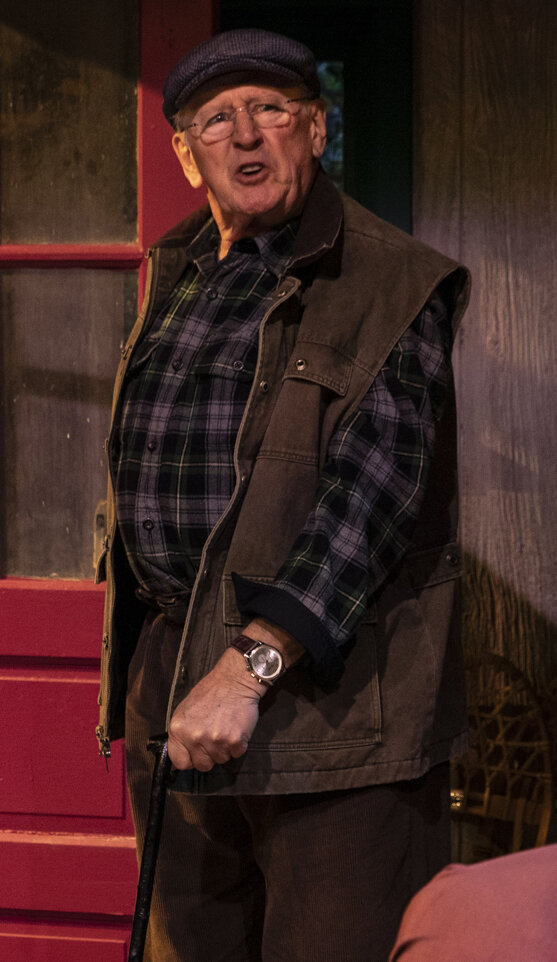

The role of 84-year-old Harry Townsend is played by 80-year-old Len Cariou, and it’s a treat to see this Tony-winning luminary of classical and musical theater on stage (he now gets more recognition for his role on TV’s Blue Bloods). Cariou has at least some audience members in tears by the time Harry walks out of that lake house door for the last time. If only the playwright, George Eastman, had more gracefully shaped the crisis that brings him to that point. Instead, Eastman has loaded the first act with too much exposition—Harry and son telling each other things they would already know—and with hackneyed “old person” laugh lines, like Harry talking about boners and farting and how he doesn’t get the kooky California lifestyle and all that modern stuff like environmentalism. Eastman also has given Harry some inauthentic, bad-punny dialogue, such as “I give good phone” and “Man should be able to fork the enemy, not spoon him.”

In the play, which is directed by Karen Carpenter, Harry’s son, Alan (Craig Bierko), is visiting from California because he has heard from his twin sister that their father has been deteriorating and probably shouldn’t continue to live alone. So there’s a lot of back-and-forth of Alan pointing out Harry’s weaknesses and Harry insisting he’s fine and would never move to a senior community. Very little actually happens in the first act, and the crucial incident of the second act occurs off stage and is merely recounted by Harry. None of this helps to create dramatic momentum.

Furthermore, the father-son relationship seems erratically drawn. Harry is more garrulous than his son, but it’s a bit of a surprise when Alan explodes at Harry later in the play for never understanding or taking an interest in him. They’ve been pretty friendly and affectionate with each other until then, and Harry has asked questions and recalled small moments from his son’s childhood and from the time Alan lived in France as a younger man.

Cariou, who plays the 84-year-old title character, is a three-time Tony nominee and a member of the Theater Hall of Fame. Photographs by Maria Baranova.

One reason Alan’s resentment does not feel conveyed effectively is that the role is underwritten. A few details about him are revealed—formerly a teacher, now in real estate; divorced, moving in with his girlfriend—but not much about his life’s journey emotionally. He often comes off like a cipher rather than somebody who has lived in the shadow of a more extroverted relative. This reserved, stuffed-shirt character is also not the easiest fit for Bierko, who has a history of playing sketchy types. (For that matter, Harry’s randiness—which the script overplays—doesn’t entirely sit well on Cariou.)

The Townsends’ cozy home is lovingly rendered by scenic designer Lauren Helpern in much detail. Perhaps too much detail: While all the books, board games and sporting equipment indicate the active life Harry once had, it’s not likely anybody would keep oars and skis inside the house.

What would be very familiar to many people, however, is the subject matter of Harry Townsend’s Last Stand: dealing with elderly loved ones, and finding them the appropriate care. (According to recent government statistics, more than 40 million Americans—16 percent of the adult population—have such a responsibility.) Harry’s resistance to leaving his home of many years and all its comforting memories is very moving, yes, but also very relatable. Having it portrayed on stage by a beloved old hand like Cariou only adds to the poignancy.

Harry Townsend’s Last Stand is at City Center Stage II (131 W. 55th St.) through April 5. Evening performances are at 7:30 p.m. Monday, Tuesday and Thursday through Saturday; matinees are at 2:30 p.m. Thursday and Saturday and 3 p.m. Sunday. Tickets are available by calling (212) 581-1212 or visiting nycitycenter.org.