Nobody involved in the production of Casablanca expected it to be a hit, let alone win the Best Picture Oscar and go on to be considered one of the quintessentially quotable classic Hollywood films. If CasablancaBox, the new behind-the-scenes ensemble drama at HERE Arts Center, is to be believed, no one really wanted to make the 1942 release either. That we’re still watching it and talking about it 75 years later proves William Goldman’s famous dictum that in Hollywood “nobody knows anything.”

Created by husband-and-wife team Sara and Reid Farrington and brought to life by a forceful cast of 16, CasablancaBox is a cornucopia blend of E! True Hollywood Story backstage tittle-tattle and DVD making-of material. With techniques lifted straight from the “Wooster Group Handbook for Doing Movies on Stage,” the play constructs a lively cross-section of early-1940s filmmaking to explore what that movie meant to its creators and an American public less than a year into World War II, as well as the darker undercurrents of American life it helped to crystallize and obscure.

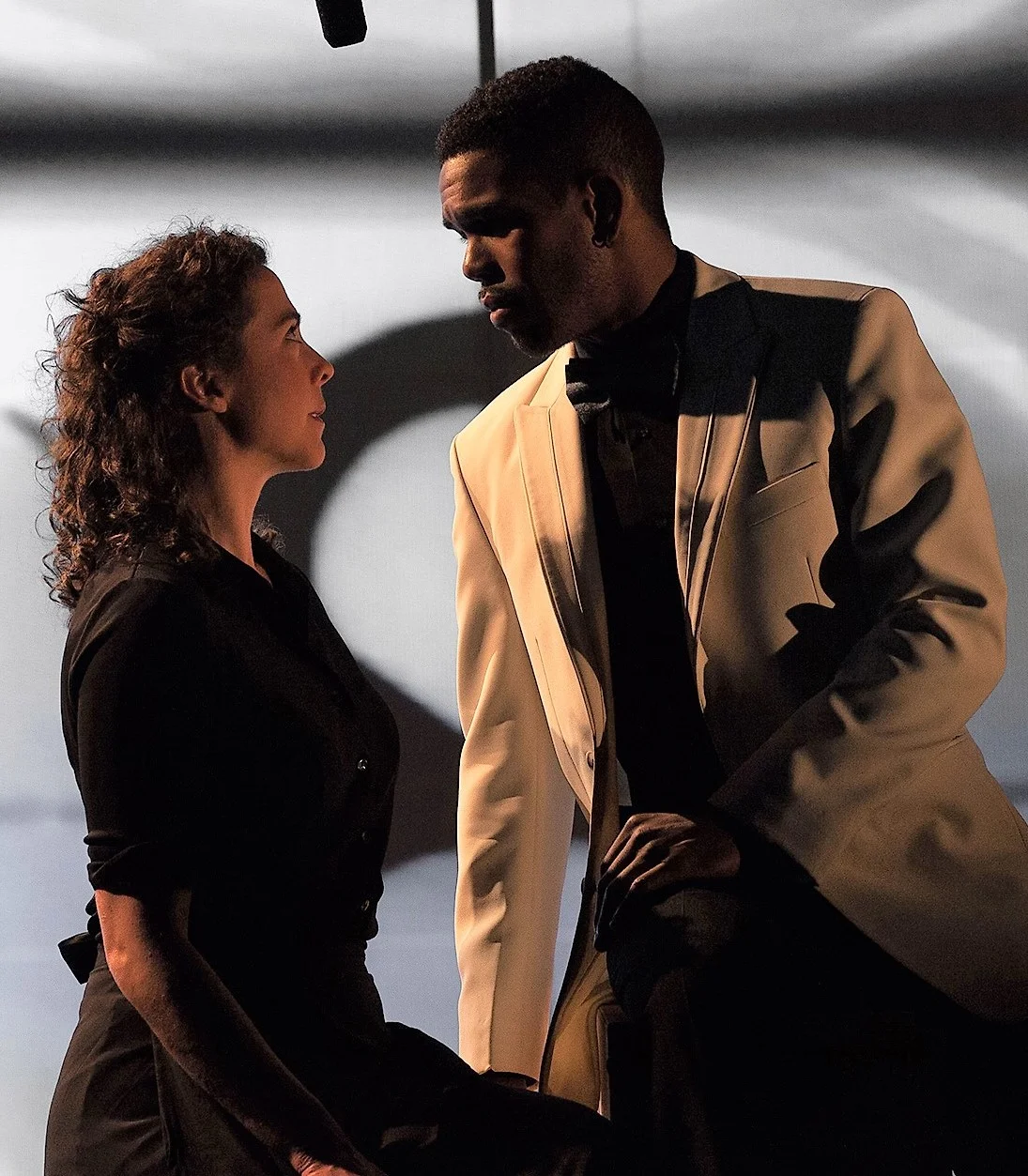

Gabriella Rhodeen plays four roles in the brief but expansive CasablancaBox at HERE. Top: Hollywood icons Ingrid Bergman (Catherine Gowl) and Humphrey Bogart (Roger Casey) shoot a romantic scene with the help of stagehand Lynn R. Guerra.

The play nearly bursts from trying to say and do so much, but is held together by its nimble staging conceit; as the actors, costumed almost entirely in black and white, mime the scenes behind actual film footage projected on precisely choreographed moving screens, the familiar-to-the-point-of-cliché film becomes novel once again.

With a brisk running time of 90 minutes, CasablancaBox is more interested in peering into people’s lives than diving deep. The Farringtons have acknowledged their artistic debt to the films of Robert Altman, and his influence is clear—as in an Altman film, the ensemble is the star; each character is treated as equally interesting and equally mysterious. Like an Altman film, this approach leads to a work that is more brain food than chicken soup for the soul.

The movie’s main players are all at crossroads in their lives and careers. Humphrey Bogart (Roger Casey) is an uncomfortable romantic lead, and his washed-up wife, Mayo Methot (Erin Treadway), keeps crashing the set like an alcoholic Norma Desmond. Ingrid Bergman (Catherine Gowl), bored in her marriage to a dentist, wants to make “important” pictures with Roberto Rossellini, her future paramour. Peter Lorre (Rob Hille) is sneaking off to his trailer to shoot up and Paul Henreid (Matthew McGloin) is still traumatized by his near escape from the Nazis. Director Michael Curtiz (who, having already directed dozens of films, would go on to make Mildred Pierce, White Christmas, and King Creole, easily the best Elvis Presley film) is brilliant but too caught up in hobnobbing with the stars to offer much support or guidance to his cast and crew.

Those at the bottom of the food chain get their say as well, and it is through their stories that both casual and not-so-casual forms of oppression are revealed. The underappreciated writers (is there any other kind?) can’t deliver an ending, blaming their late pages on having “a dame in the writer’s room.” Two German actors, stars at home, are reduced to playing Nazi stooges because “in America, you sound like Nazi, so you are Nazi.”

Bergman (Gowl) and Bogie (Casey) smolder onscreen but struggle off. Photographs by Benjamin Heller.

Then there’s Dooley Wilson (Toussaint Jeanlouis), Sam of “Play it again” fame, whom Jack Warner “bought” from David O. Selznick, and who is willing to work for humiliatingly low pay because at least he’s not cast as a Pullman porter. For all the actors, the studio system is indentured servitude, if not legal slavery, and the actors of color feel its effects most keenly.

CasablancaBox is not so much color-blind as color-indifferent. By casting actors of color as the white Bogey and Curtiz, the play repeats Hamilton’s trick of reminding the audience that race isn’t actually a thing. It does Hamilton one better, though, as the actors playing Lorre, Bergman, Bogey, and Curtiz slip in and out of their “real” accents (Casey’s Bogart is uncanny); if movies like Casablanca tend to smooth out differences and naturalize the unnatural, the theater is here to remind the audience that identity is just one big performance.

Though Rick’s famous mantra that he “sticks (his) neck out for nobody” is often viewed as a metaphor for American reluctance to enter the war, the characters of CasablancaBox see the movie’s hopeful ending as proof that “America will feel a moral obligation to stick its neck out and save the whole world.” In a week when the military has once again begun bombing Syria, CasablancaBox, like the movie whose creation it details, has taken on chilling symbolic resonance. We’ll always have Casablanca, but real life continually insists on intruding, making it hard to believe that escapist entertainment amounts to a hill of beans in this crazy world.

CasablancaBox plays through April 29 at HERE Arts Center. Evening performances are at 8:30 p.m. Wednesday through Saturday. Matinees are at 4 p.m. Saturday and Sunday. For tickets, call (212) 352-3101 or visit here.org.