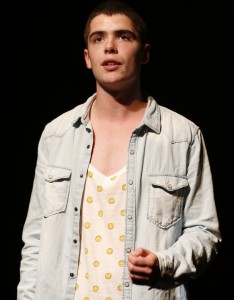

The couple one first meets in the Debate Society’s production of Jacuzzi are as laid-back as can be. Helene and Derek (Hannah Bos and Paul Thureen, respectively, who are also the co-authors) are lounging in the Jacuzzi of the title, taking in their surroundings—a Colorado chalet with knickknacks about. Outside are winter light and snow, and one’s first impression is that Derek and Helene, who are a couple, are renting the chalet (a slant-roofed building, designed by Laura Jellinek, that displays objets d’art on shelves built into the roof interior). When Chris Lowell’s athletic Bo arrives unexpectedly, he is surprised to find them there, but then he’s a day early. He has come for the weekend to join up with his father, Robert, from whom he has been estranged.

Bo is a troubled young man; after drinking too much and joining Derek and Helene in the hot tub in a sexually charged scene (skillfully directed by Oliver Butler, who is also credited with “development”), he starts to spill secrets but thinks better of it. Enough has been said: there was an affair with an older Frenchwoman who had a child; somehow they ended up in Romania, where something terrible happened that causes him anguish.

To avoid spoiling what happens next, let’s just say that nobody is who or what they seem in this twisty, exhilarating, and disturbing work. There’s a hint of something amiss when, on the following morning, Bo learns that Derek’s name is Erik, not Derek as he thought, and apparently blames his mistake on drink—though it’s not a mistake. There are echoes of Tartuffe or Jean Genet’s The Maids as Erik and Helene, who have been sprucing up the chalet for Robert, ingratiate themselves with him.

The script is smartly developed, teasing out secrets in the characters’ stories. A throwaway reference from Robert explains that the chalet, long in his ex-wife Jackie’s family, came to him in their divorce “’cause of what I had over her head.” Helpful and likable as Helene and Erik seem initially, their presence grows more sinister. A periodic voice-over reveals the cheery Helene as more complex and in charge; the physically imposing Erik takes cues for his behavior from her. They are well behaved, but are they for real?

As Robert, Peter Friedman is alternately exulting and embittered, comically complaining while denying he’s complaining; a flash of anger at his son, revealed in a single line, is a clue to the depth of discord in their relationship. He's also a man who buys what he wants. Robert and Jackie were psychologists, and are now successful authors, and their neglect and abuse of Bo is slowly revealed. “When my parents were on Donahue they locked me in the hotel room and told me not to watch TV,” Bo says, as his father protests. And later, as Bo describes a childhood birthday party, his father lets drop that he was a guinea pig: it was “one of these parties where Jackie and I were testing interactions.”

Bo’s upbringing is surely a reason for his lack of empathy with others—he suggests that Helene and Erik’s working life is comparable to an internship he once had. Lowell deftly shows that Bo is an erratic, emotional mess; he has lost the ability to trust anyone, and his parents are to blame. But his suspicious nature also heightens his awareness of danger, and director Butler throughout keeps the suspense building.

As well as Jacuzzi plays out, it leaves open many questions. Must the price of success be to pervert or destroy natural emotions? Is the amorality of the wealthy more easily spotted than that of the working class? And does their ability to escape justice because of their resources make them fair prey? But then, the best drama always leaves room for debate, and what better group for Ars Nova to present a commission to than the Debate Society? Jacuzzi should ensure them further support.

Jacuzzi plays through Nov. 15 at Ars Nova on the following schedule: Mon.-Wed. at 7 p.m.; Thurs.-Sat. at 8 p.m. Matinees are Saturdays at 2 p.m. For tickets, call Ovation Tix at 866-811-4111 or visit arsnovanyc.com.